마하붑 호세인 프린스 , 사디아 라흐만 토루 , 정임주 , 이선희

다양한 족저근막염용 양말의 니트 구조 및 족저압 비교 분석

Comparative Analysis of Knitting Structures and Plantar Pressure in Various Plantar Fasciitis Socks

Mahabub Hossain Prince, Sadia Rahman Toru, Imjoo Jung, Sunhee Lee

Abstract: This study evaluated three types of plantar fasciitis socks (PFS), PFS01, PFS02, and PFS03, to identify optimal knit structures for support and pressure relief. Each sock was segmented into 12 to 13 anatomical regions and analyzed for knit type, thickness, and stitch density. PFS03 featured the most complex design with a combination of plain, rib, and jacquard knits applied to multiple zones, particularly in the heel and ankle, to enhance zonal compression and joint stabilization. PFS01 had a simpler structure with moderate compression, while PFS02 applied targeted support using increased stitch density. Thickness measurements revealed design-specific cushioning, with PFS01 emphasizing the metatarsal region, PFS02 reinforcing the ankle area with its thickest section at reaching 3.07 mm, and PFS03 focusing on heel protection with thickness values exceeding 2 mm. Plantar pressure analysis using a symptomatic subject confirmed that all socks reduced peak pressure compared to barefoot walking. PFS02 showed the most significant reduction in highstress zones such as medial forefoot and heel, along with improved contact area and pressure distribution. These findings suggest that PFS02 offers the most effective knit configuration, providing enhanced compression, ankle stability, and pressure relief.

Keywords: plantar fasciitis socks , knitting structure , thickness of socks , plantar pressure analysis

1. Introduction

Plantar fasciitis is one of the most common causes of heel pain and involves inflammation of the plantar fascia, a thick band of tissue that stretches from the heel to the toes and supports the arch of the foot [1]. This condition typically results from repetitive stress and strain on the fascia, causing microtears that lead to inflammation, discomfort, and stiffness [2]. Plantar fasciitis is especially prevalent among athletes, such as runners, as well as individuals who spend long hours on their feet or participate in high-impact activities, like standing for extended periods or engaging in intense physical exertion [3,4]. According to Glazer [3], this condition affects millions of people annually, significantly impacting their ability to walk, exercise, or carry out daily activities. Effective management of plantar fasciitis typically involves a combination of rest, stretching exercises, physical therapy, and, most importantly, wearing appropriate footwear that reduces pressure on the fascia while promoting foot stability and comfort [5−8]. Footwear design also plays a critical role in reducing plantar strain and redistributing pressure, especially for individuals with flatfoot or biomechanical abnormalities [9−11]. For comprehensive management, integrating appropriate supportive gear and evidence-based rehabilitation protocols is crucial to achieving long-term recovery [12,13].

Plantar fasciitis socks have become increasingly popular due to their ability to provide targeted support, cushioning, and compression to the foot [14,15]. These socks are specifically designed to reduce plantar pressure, minimize strain on the plantar fascia, and improve overall foot comfort during both rest and activity [16,17]. Strategic knitting structures and the use of advanced materials contribute to an even distribution of pressure across the foot, helping to alleviate stress points and enhance overall stability [18]. A key design feature of these socks is the incorporation of region-specific thickness variations and compression zones, particularly targeting highstrain areas such as the heel, arch, and forefoot [18,19]. These zones are critical for redistributing pressure, reducing localized swelling, and promoting circulation—factors that collectively support the structural integrity of the foot during movement [20,21]. The effectiveness of plantar fasciitis socks ultimately depends on their optimal balance of compression, thickness, and flexibility, ensuring that they provide sufficient support without restricting mobility [22,23].

The effectiveness of socks can be evaluated through plantar pressure analysis. Plantar pressure refers to the distribution of force across the bottom surface of the foot during movement and plays a critical role in both injury prevention and performance, particularly in individuals with plantar fasciitis [24]. Abnormal pressure patterns—such as excessive loading on the heel or forefoot—can exacerbate pain and tissue strain [25]. The structural design of socks, including thickness, yarn type, and knitting pattern, can influence how pressure is distributed across metatarsal regions, particularly under highstress zones [26,27]. Recently, Martinez Nova et al. [19] reported that biomechanical socks provided clinical improvement in planter fasciitis sympotms by enhancing comfort and reducing foot pain through targeted support and pressure redistribution. In addition, Soltanzadeh et al. [18] found that variations in sock structure significantly influenced planter dynamic pressure distribution, helping reduce localized pressure on critical foot regions in individuals with planter fasciitis. Also the compression therapy, when integrated into plantar fasciitis socks, has been shown to provide several benefits beyond just comfort [28]. Compression can help enhance circulation, which is essential for reducing swelling and promoting the healing of inflamed tissues [23]. By applying controlled pressure to the foot, the sock encourages improved blood flow, which aids in delivering essential nutrients to the affected areas and removing metabolic waste products [29]. This reduction in swelling and improvement in circulation can significantly reduce the symptoms associated with plantar fasciitis, such as pain, stiffness, and discomfort [29]. Furthermore, the application of localized compression to high-pressure areas—such as the heel and arch—can improve proprioception, helping individuals maintain better control over their foot movements [28]. Compression zones are carefully placed to target these areas, providing relief where it is most needed [23]. However, it is important to note that the ideal balance of compression, thickness, and material composition may vary from person to person, which is why more detailed research is necessary to identify the most effective designs for managing plantar fasciitis [29]. Therefore, further research is necessary to determine the optimal combination of compression level, stitch density, and material characteristics that will enable plantar fasciitis socks to offer the most effective support and relief for individuals with this condition [30].

Thus, the purpose of this study was to identify the optimal sock design for plantar fasciitis support. It focused on analyzing differences in size, knitting structure, thickness, and stitch count across various sock sections. By comparing these structural features, the study aimed to understand their impact on comfort and support. Additionally, a plantar pressure test was conducted on a subject with symptoms of plantar fasciitis. This allowed evaluation of each sock’s effectiveness in reducing pressure and enhancing foot stability.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

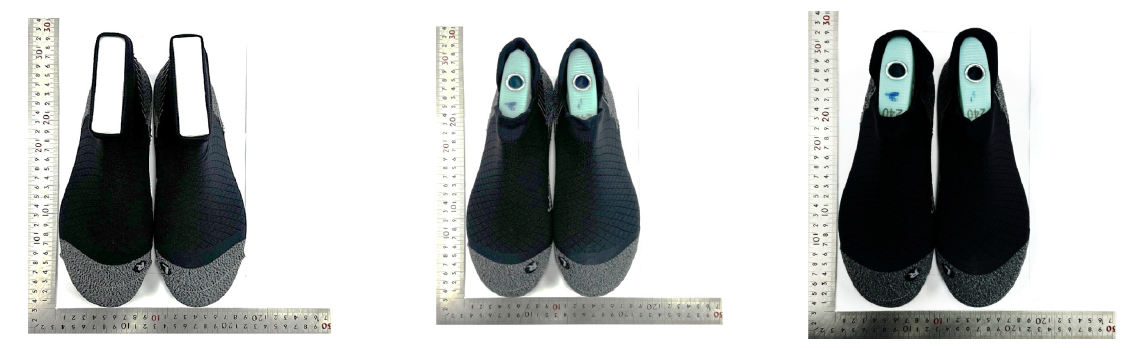

Table 1 presents three types of socks designed specifically for plantar fasciitis support that were selected and analyzed in this study. The samples included two models from Feetures (USA)—PFS01 and PFS02—and one model from OS1st (USA)—PFS03. All three socks were black in color but varied slightly in fiber composition, design features, and weight. PFS01 was composed of 92% nylon and 8% spandex, offering moderate elasticity and structural support, with a total weight of 16.9 g. PFS02, made from 91% nylon and 9% spandex, provided slightly greater stretch and was the lightest among the three, weighing 14.9 g. In contrast, PFS03, had the highest elasticity due to its composition of 89% nylon and 11% spandex, and weighed 15.7 g.

Table 1.

| Sample code | Plantar fasciitis socks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS01 | PFS02 | PFS03 | ||

| Company | Features (USA) | OS1 st (USA) | ||

| Fiber composition | 92% Nylon | 91% Nylon | 89% Nylon | |

| 8% Spandex | 9% Spandex | 11% Spandex | ||

| Weight (g) | 16.9 | 14.9 | 15.7 | |

| Image | Top |  | ||

| Inside |  | |||

| Outside |  | |||

| Bottom |  | |||

2.2. Part Distributrion for Three Types of Plantar Fasciitis Socks

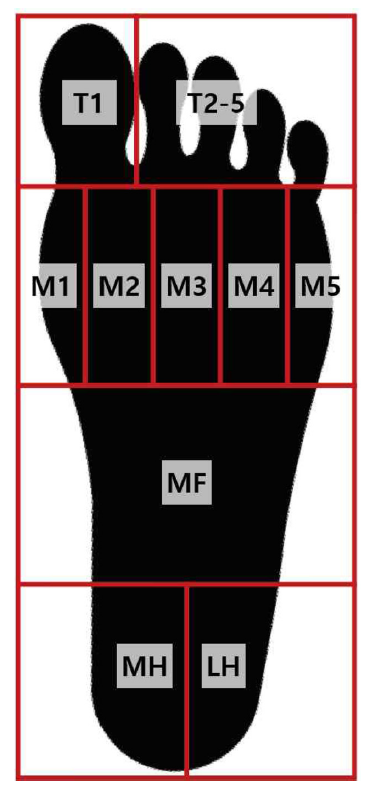

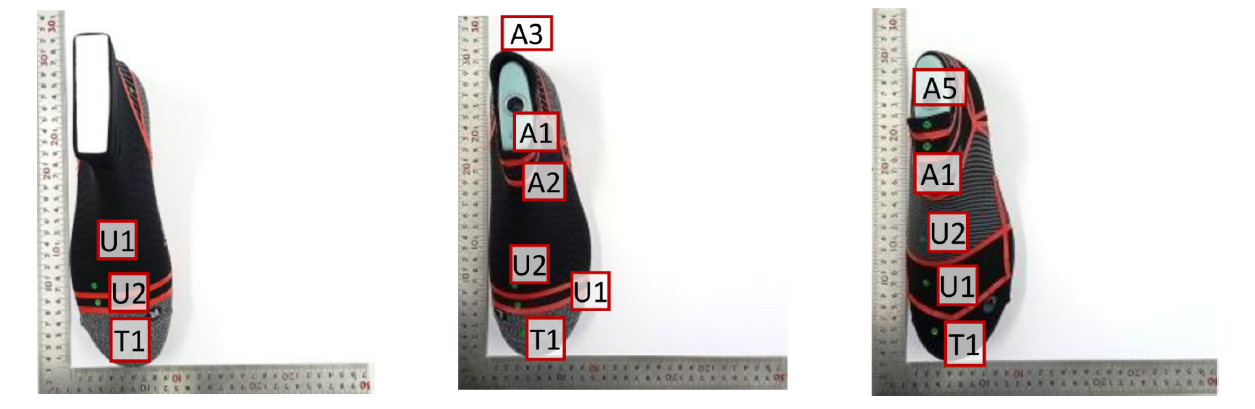

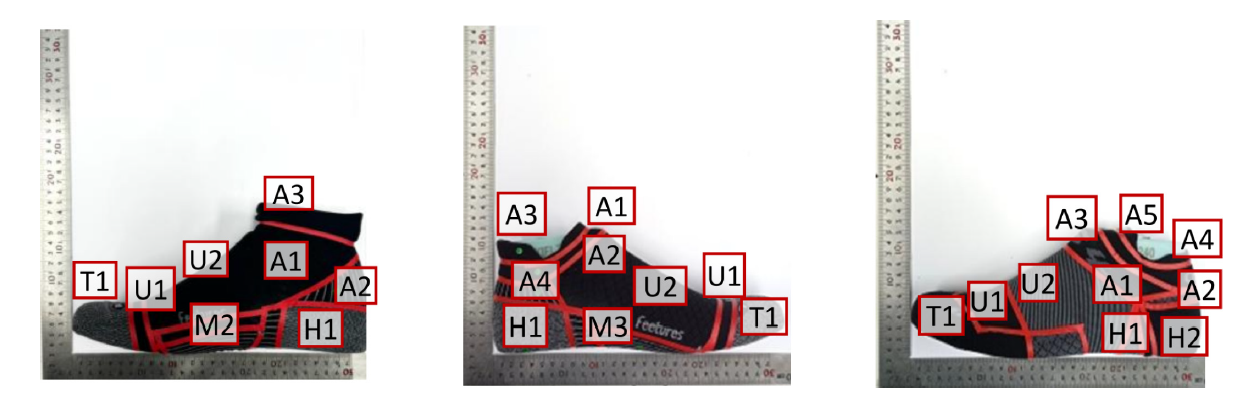

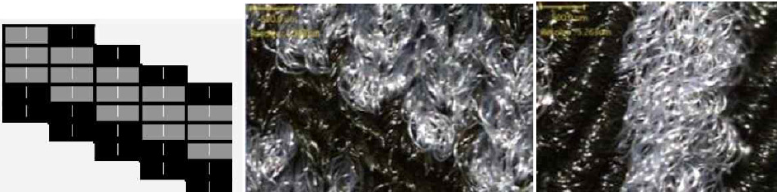

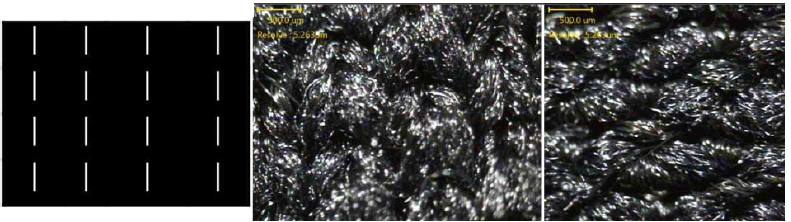

Figure 1 shows information for analyzing the structure it is divided into five areas: toe (T), upper (U), meta (M), heel (H), and ankle (A). These zones were clearly marked to enable consistent comparison. Although all three sock models were designed differently, each was analyzed using the same fivepart division to evaluate variations in structure and support.

Size analysis measurements were taken in millimeters (mm) and then converted to centimeters (cm) to standardize the data. This approach allowed for accurate comparison of the dimensional characteristics of five zone.

2.3. Characterization

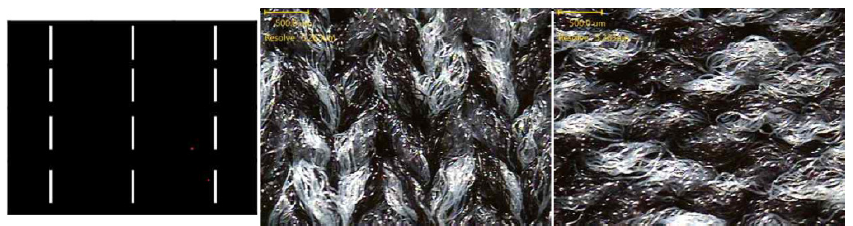

For analyzing three types of plantar fasciitis socks, the thickness was measured using an absolute digimatic caliper (CD- 20CPX, Mitutoyo, Japan). The thickness of each sample was measured in millimeters (mm). The surface structure and knitting structure of the samples were examined by morphology analysis, using a microscope (NTZ-6000, Nextecvision Co. Ltd., Korea) at a magnification of × 4.55. The stitch count was confirmed as course × wales per inch2 and course × wales per sample.

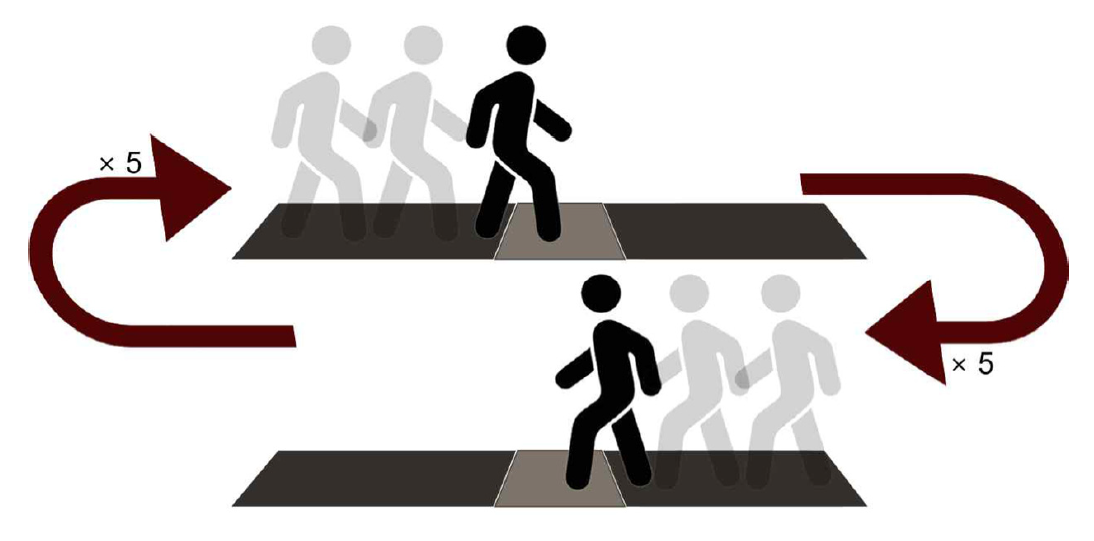

Additionally, a plantar pressure analysis was conducted to evaluate the actual wear ability of the socks. Plantar pressure analysis was performed using a plantar pressure analyzer (Materialise, Belgium) and the Foot Scanner program (Alchemaker, USA). Two female participants with normal feet were selected for the study. Physical informations of two participants are shown in Table 2. Prior to conducting the plantar pressure measurements, participants were thoroughly informed about the study's purpose and procedures, and voluntarily signed a consent form authorized by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Ethical clearance for this research was granted by the IRB of Dong-A University (Approval No. 2-1040709-AB-N- 01-202501-HR-003-02). Measurements were taken under barefoot (BF) and sock conditions (PFS01, PFS02, PFS03) while walking motion. The walking motion was measured by having participants walk five round trips on an 8-meter mat by turning at each end, recording five times for the left foot and five times for the right foot, and using the average values for analysis. An example of a walking motion is shown in Figure 2. The analysis confirmed the plantar force diagram, foot zone diagram, and peak pressure during walking. In particular, for the foot zone diagram, the plantar force diagram was divided into 10 zones and checked. The 10 zones are shown in Table 3. The peak pressure results were analyzed by calculating the mean and standard deviation. And then, statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM, USA), with a significance threshold set at P < 0.05. The 10 data of 5 left foot and 5 right foot were used, and a repeated measures ANOVA was applied to evaluate differences in plantar pressure distribution across the four conditions. In addition, Tukey HSD method was applied for post-hoc analysis, and the significance level was set at 0.05.

Table 2.

| Participant code | Participant | Age | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | Foot size (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Subject 1 | 29 | 155.1 | 60 | 225 |

| S2 | Subject 2 | 31 | 159.4 | 65 | 230 |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Part Analysis for Three Types of Plantar Fasciitis Socks

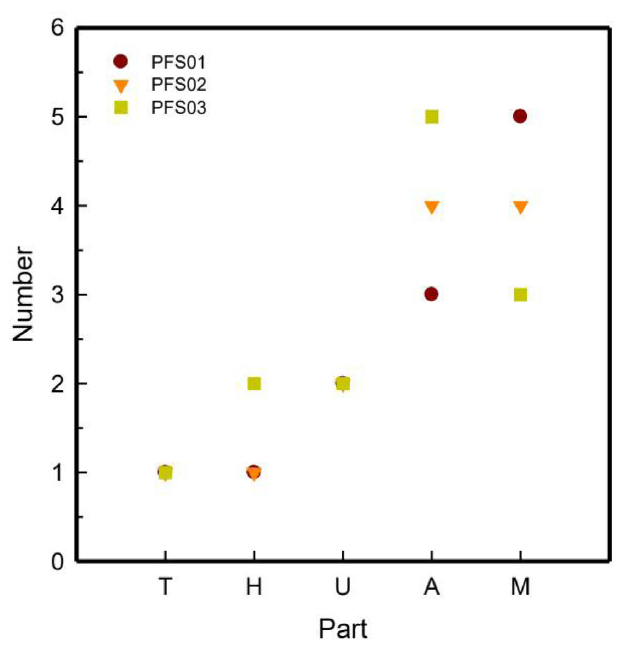

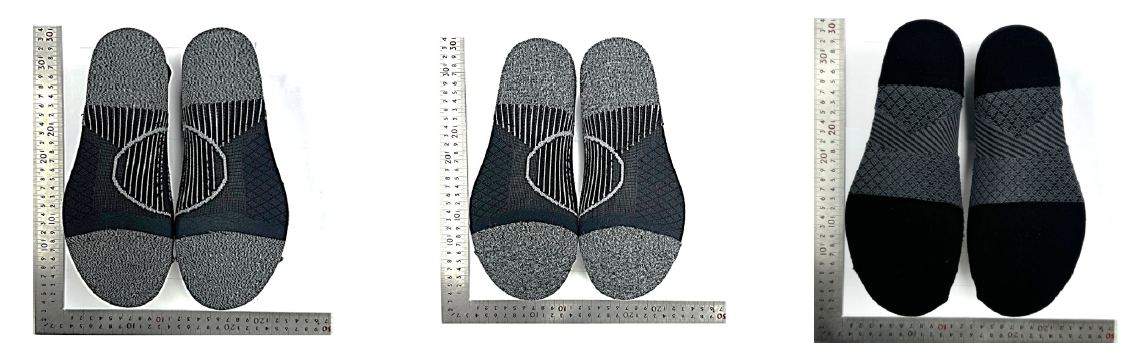

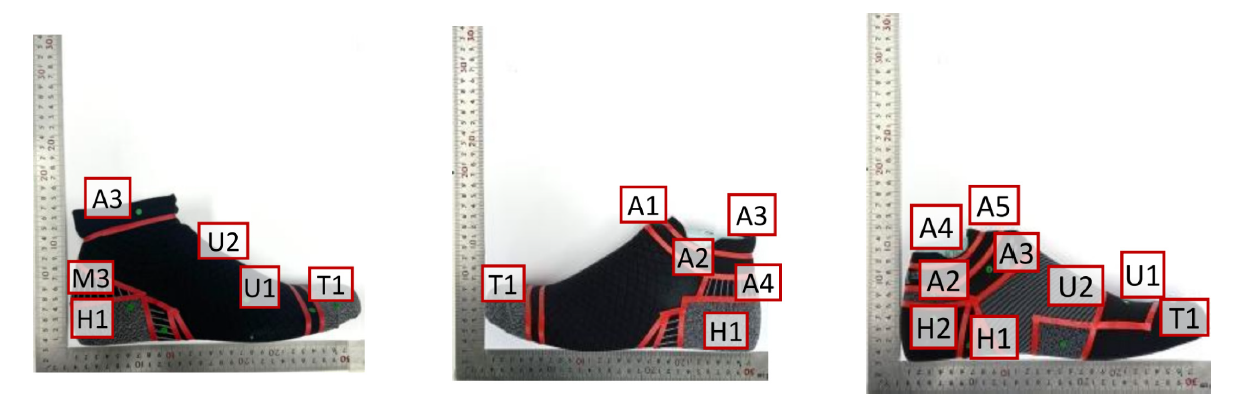

Table 4 appeared a detailed part analysis of three types of plantar fasciitis socks PFS01, PFS02, and PFS03 based on their visual knit structure and functional design. Figure 3 shows the part distribution analysis of three types of plantar fasciitis socks PFS01, PFS02, and PFS03 categorized into five key anatomical zones of T, M, H, U, and A.

Table 4.

| Plantar fasciitis socks | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PFS01 | PFS02 | PFS03 | |

| Top |  | ||

| Inside |  | ||

| Outside |  | ||

| Bottom |  | ||

The structural composition of the plantar fasciitis sock models PFS01, PFS02, and PFS03 revealed deliberate design variations aimed at optimizing foot support. PFS01 consisted of 12 parts: 1 toe (T1), 5 metatarsal (M1–M5), 1 heel (H1), 2 upper (U1–U2), and 3 ankle parts (A1–A3). PFS02 shared the same number of total parts but featured fewer metatarsal (4) and more ankle parts (4), suggesting a design shift toward increased ankle support. PFS03 showed the most complex structure with 13 parts, including dual heel parts (H1–H2) and five ankle parts (A1–A5), indicating enhanced cushioning and joint support. The toe part supported toe mobility and propulsion, while the metatarsal sections distributed plantar pressure and aided forefoot loading. The heel part cushioned ground impact and reduced strain on the plantar fascia. The upper segments helped maintain sock position through mild compression, and the ankle parts stabilized joints and enhanced proprioceptive feedback [7, 17,18]. The higher segmentation in PFS03, especially in the ankle and heel zones, reflected a more advanced support system designed to improve pressure redistribution, joint alignment, and plantar fascia tension relief [19].

As shown in Figure 3, all three sock types included one part in the T and H regions, showing a consistent design for basic foot coverage and stabilization. However, notable variation was observed in the M, A, and U zones. The M region, which plays a vital role in foot propulsion and support, has the highest segmentation in PFS01 5 parts, followed by PFS02 4 parts, and PFS03 3 parts [20]. This suggests that PFS01 was structurally for forefoot and midfoot compression and support [8]. In the Ankle A region, PFS03 showed the highest number of parts 5, followed by PFS02 4 and PFS01 3, indicating increased design complexity likely aimed at better ankle stabilization and proprioceptive feedback [17]. The U zone showed consistent segmentation in PFS02 and PFS03 2 parts each, while PFS01 had only 1 part, reflecting a more minimal upper support structure. The increased segmentation in the Metatarsal and Ankle areas was likely functional. These regions were critical in plantar fasciitis support, as more structured zones can enhance pressure distribution, arch lift, joint stability, and foot alignment [21]. Higher part counts in these areas allow for finer control of compression, which is beneficial in reducing plantar fascia strain and improving comfort during activity or rehabilitation [22].

3.2. Structure Analysis for Three Types of Plantar Fasciitis Socks

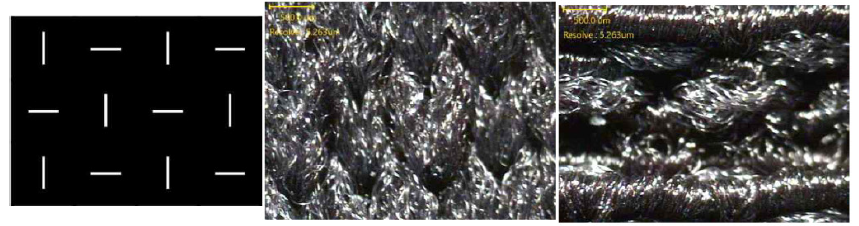

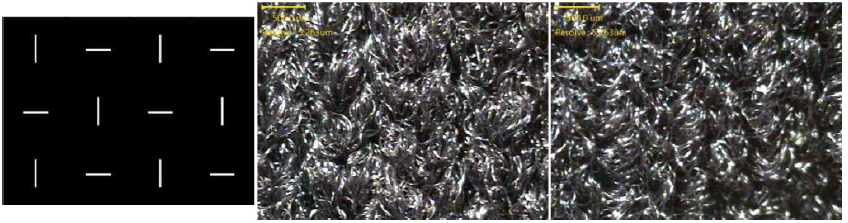

Tables 5−7 presented a comparative structural and stitch density analysis of three plantar fasciitis support socks—PFS01, PFS02, and PFS03—highlighting their knit structures and compression zoning across segmented regions.

Table 5.

| Part | Size (mm2) | Structure | Stitch count | Repeat unit | Surface Image | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course× Wales / inch2 | Course× Wales per sample | Front | Back | |||||

| TOE | T1 | 104 × 53 | Plain | 35 × 70 | 145 × 148 |  | ||

| META | M1 | 100 × 12 | Plain | 25 × 55 | 100 × 26 |  | ||

| M2 | 80 × 67 | Plain rib | 30 × 40 | 9 × 107 |  | |||

| M3 | 72 × 32 | Plain/Jacquard | 30 × 50 | 86 × 51 |  | |||

| M4 | 64 × 80 | Plain rib | 35 × 55 | 93 × 176 |  | |||

| M5 | 37 × 93 | Plain | 25 × 55 | 37 × 204 |  | |||

| HEEL | H1 | 78 × 103 | Plain | 35 × 70 | 109 × 288 |  | ||

| UPPER | U1 | 100 × 12 | Plain | 25 × 55 | 100 × 26 |  | ||

| U2 | 85 × 93 | Plain | 35 × 40 | 102 × 148 |  | |||

| ANKLE | A1 | 52 × 165 | Plain | 30 × 40 | 62 × 264 |  | ||

| A2 | 42 × 95 | Plain/Jacquard | 30 × 50 | 50 × 190 |  | |||

| A3 | 91 × 19 | Plain rib | 35 × 70 | 127 × 53 |  | |||

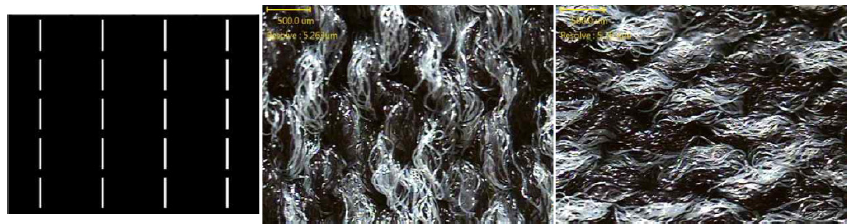

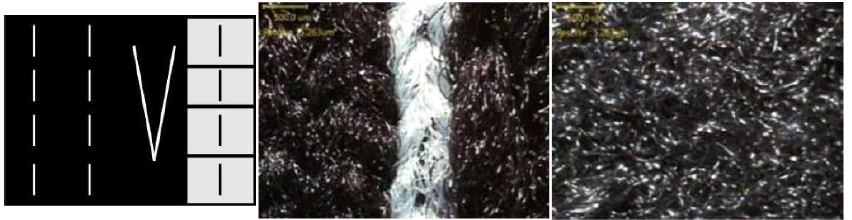

Table 6.

| Part | Size (mm2) | Structure | Stitch count | Repeat unit | Surface Image | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course× Wales / inch2 | Course× Wales per sample | Front | Back | |||||

| TOE | T1 | 99 × 96 | Plain | 40 × 70 | 158 × 268 |  | ||

| META | M1 | 93 × 8 | Plain | 60 × 70 | 223 × 22 |  | ||

| M2 | 81 × 52 | Plain rib | 30 × 40 | 162 × 124 |  | |||

| M3 | 78 × 38 | Plain/Jacquard | 30 × 50 | 124 × 121 |  | |||

| M4 | 134 × 125 | Plain rib | 35 × 55 | 187 × 300 |  | |||

| HEEL | H1 | 103 × 69 | Plain | 35 × 70 | 164 × 193 |  | ||

| UPPER | U1 | 119 × 11 | Plain | 60 × 70 | 285 × 30 |  | ||

| U2 | 94 × 124 | Plain | 35 × 60 | 131 × 297 |  | |||

| ANKLE | A1 | 105 × 35 | Plain rib | 40 × 80 | 164 × 193 |  | ||

| A2 | 89 × 17 | Plain rib | 50 × 80 | 178 × 54 |  | |||

| A3 | 68 × 12 | Plain rib | 40 × 80 | 108 × 38 |  | |||

| A4 | 91 × 20 | Plain/Jacquard | 40 × 80 | 145 × 64 |  | |||

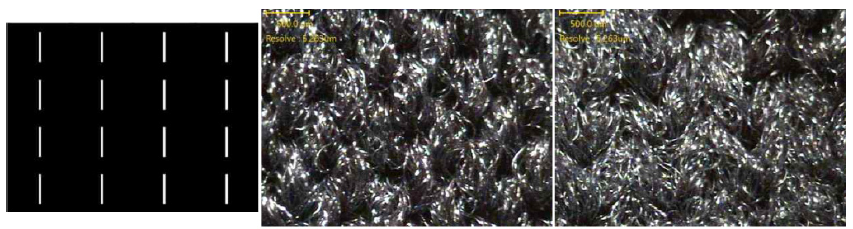

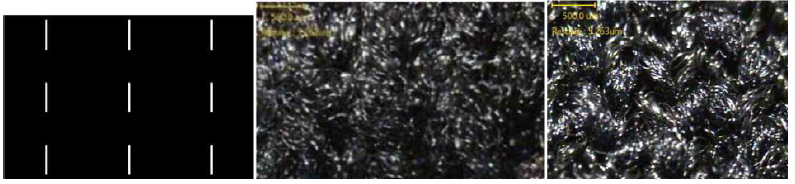

Table 7.

| Part | Size (mm2) | Structure | Stitch count | Repeat unit | Surface Image | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course× Wales / inch2 | Course× Wales per sample | Front | Back | |||||

| TOE | T1 | 107 × 128 | Plain rib | 50 × 115 | 214 × 588 |  | ||

| META | M1 | 93 × 58 | Plain/Jacquard | 25 × 55 | 130 × 139 |  | ||

| M2 | 102 × 32 | Plain rib | 30 × 40 | 204 × 44 |  | |||

| M3 | 89 × 38 | Plain | 30 × 50 | 124 × 91 |  | |||

| HEEL | H1 | 111 × 7 | Plain/Jacquard | 35 × 70 | 133 × 11 |  | ||

| H2 | 106 × 60 | Plain rib | 35 × 70 | 190 × 192 |  | |||

| UPPER | U1 | 82 × 30 | Plain | 40 × 60 | 131 × 72 |  | ||

| U2 | 100 × 84 | Plain rib | 35 × 55 | 220 × 117 |  | |||

| ANKLE | A1 | 122 × 21 | Plain/Jacquard | 40 × 55 | 195 × 46 |  | ||

| A2 | 98 × 18 | Plain/Jacquard | 45 × 60 | 176 × 43 |  | |||

| A3 | 98 × 16 | Plain/Jacquard | 60 × 70 | 235 × 44 |  | |||

| A4 | 79 × 15 | Plain rib | 70 × 90 | 221 × 54 |  | |||

| A5 | 61 × 15 | Plain rib | 70 × 90 | 170 × 43 |  | |||

PFS01 consisted of 12 parts, primarily constructed using plain knit structures in regions such as T1, M1, M5, H1, U1, and U2. M2 and M4 employed plain rib knit, while M3 and A2 featured plain/jacquard patterns. A1 was also plain knit, and A3 used plain rib, indicating a basic yet intentional distribution of structural variation. This design offered minimal compression, suitable for general comfort and flexibility [18]. The stitch density in PFS01 ranged moderately, with course × wales/in2 values between 25 × 40 and 35 × 70, providing essential support in the toe and heel areas and moderate compression at the ankle [4,15]. PFS02 maintained the same number of regions but implemented a more refined structural strategy. Plain knit was used in areas such as T1, M1, H1, U1, and U2 to maintain baseline comfort. M2, M4, and A1 through A3 were constructed with plain rib knit, while M3 and A4 incorporated plain/jacquard designs. This configuration enhanced localized support and introduced targeted compression zones. Stitch densities increased notably in this sample, with metatarsal M1 at 60 × 70, upper U1 at 60 × 70, and ankle zones reaching up to 50 × 80, reflecting improved compression and structural efficiency for plantar support [9, 13,18]. PFS03 emerged as the most complex design, featuring 13 segmented parts. T1, M2, H2, U2, A4, and A5 were knit with plain rib to provide dynamic support, while M3 and U1 remained in plain knit for comfort in less critical pressure areas. M1, H1, and A1 through A3 incorporated plain/jacquard patterns, emphasizing zonal compression. This advanced structural zoning was reinforced by the highest stitch densities observed, with the toe area T1 at 50 × 115 and ankle components A4 and A5 peaking at 70 × 90, enabling precise pressure distribution and anatomical conformity [25,28].

3.3. Thickness Analysis for Three Types of Plantar Fasciitis Socks

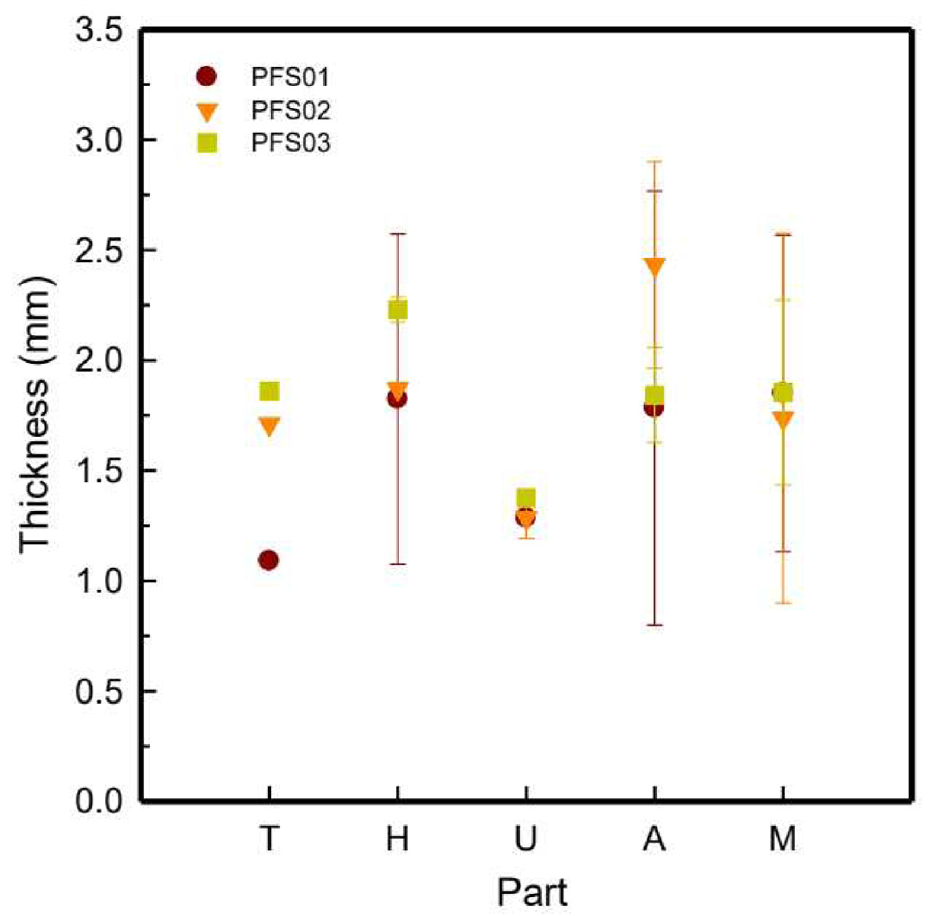

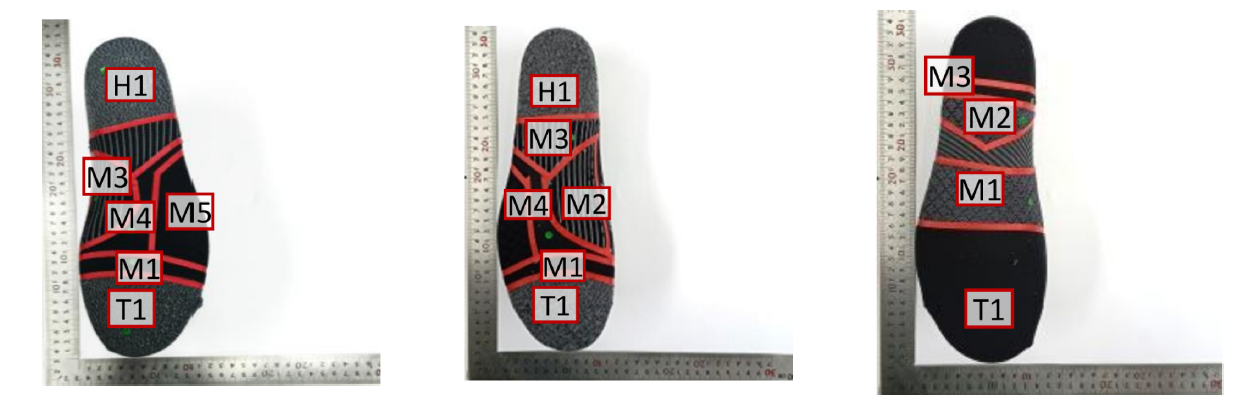

Table 8 indicates the detailed thickness values of various foot regions for the three plantar fasciitis support socks PFS01, PFS02, and PFS03. Figure 4 shows a graphical comparison of average thickness by part toe, meta, heel, upper and ankle highlighting the variation across designs.

Table 8.

| Status | S1 | S2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plantar force | Foot zone | Plantar force | Foot zone | |

| BF |  | |||

| PFS01 |  | |||

| PFS02 |  | |||

| PFS03 |  | |||

In PFS01, the thickest region was the metatarsal M3 at 2.94 ± 0.02 mm, followed by the ankle A2 at 2.91 ± 0.05 mm, while the toe T1 and ankle A3 were the thinnest at 1.09 ± 0.03 mm. PFS02 exhibited the greatest ankle thickness, with A1 measuring 3.07 ± 0.15 mm and M3 also being relatively thick at 2.92 ± 0.11 mm, whereas the toe and upper regions remained thinner, with T1 at 1.71 ± 0.05 mm and U1 at 1.22 ± 0.07 mm. In PFS03, the heel emerged as the thickest area, with H1 measuring 2.27 ± 0.07 mm and H2 at 2.19 ± 0.09 mm, indicating enhanced shock absorption [23, 29]. This was followed by the metatarsal region M3 at 2.07 ± 0.02 mm and ankle segments reaching up to 1.99 ± 0.07 mm. In PFS01 and PFS02, the A region showed the highest average thickness, followed by the H, M, T, and U regions. For PFS03, the H zone was the thickest, followed by M, A, T, and U. This pattern supported the structural focus on pressure-bearing areas. These findings indicated that differences in regional thickness reflected varied functional design strategies tailored to plantar fasciitis relief, with each sample prioritizing specific zones to enhance targeted protection and comfort [23, 29,30].

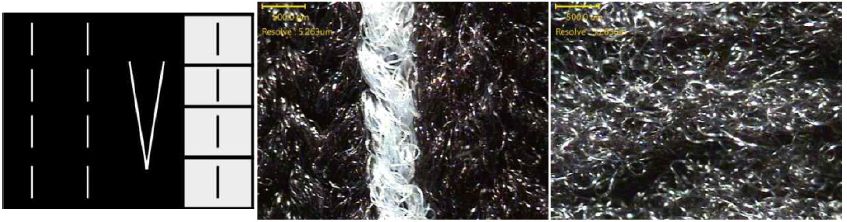

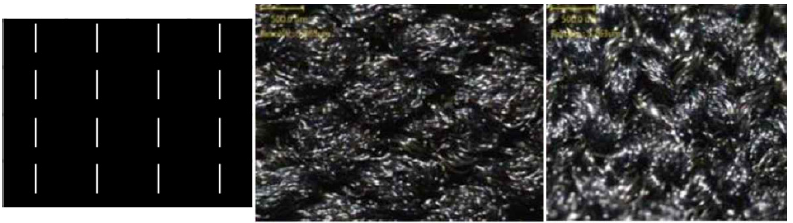

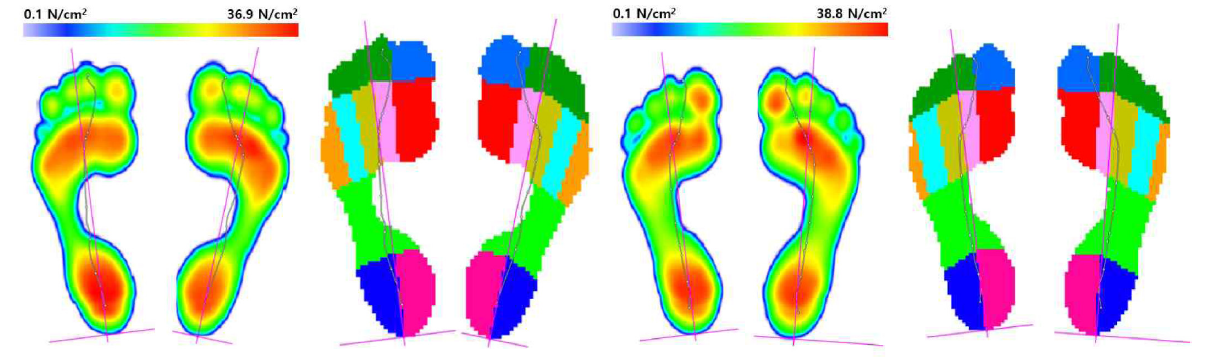

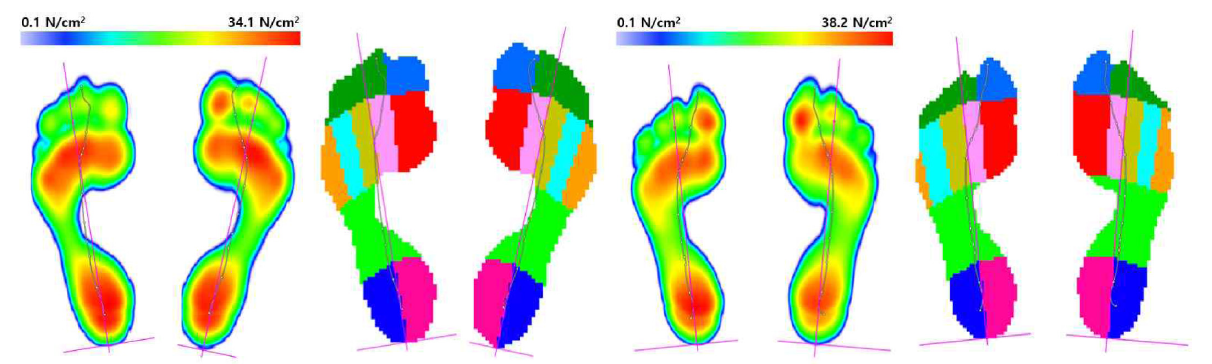

3.4. Plantar Pressure Analysis of Three Types of Plantar Faciitis Socks

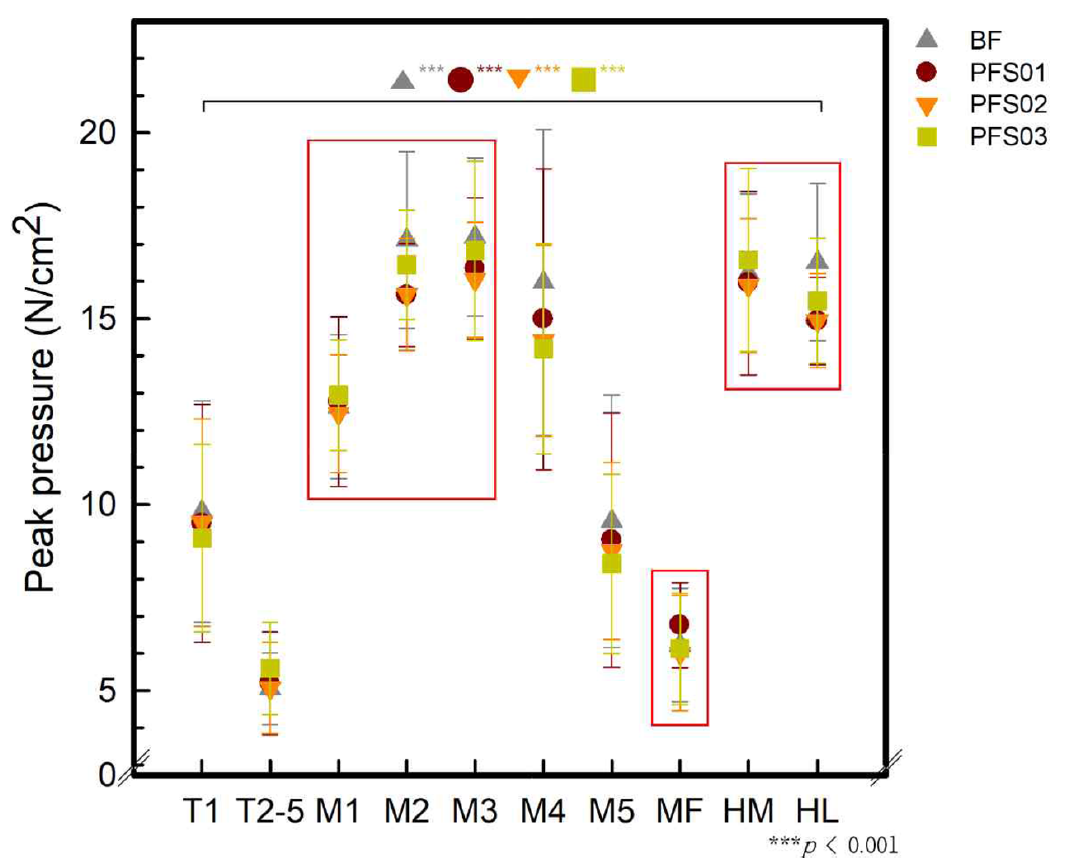

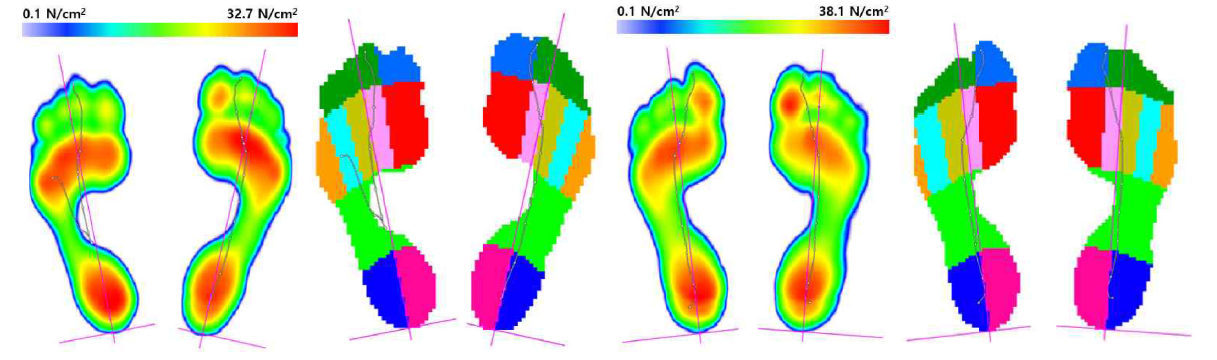

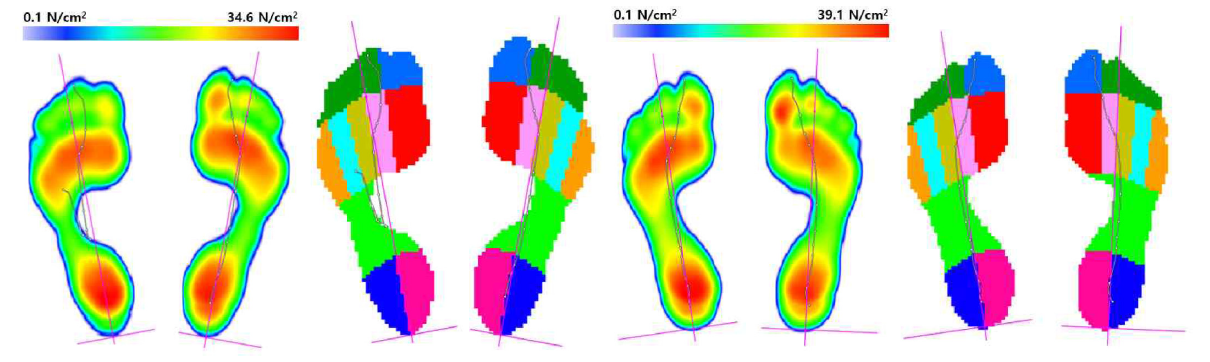

Table 8 presents the plantar force distribution and corresponding diagrams divided into ten zones during walking, both in barefoot condition and while wearing three types of plantar fasciitis socks. Table 9 and Figure 5 indicates the average peak pressure values measured in each of the 10 zones under the four different conditions during gait.

Table 9.

| BF | PFS01 | PFS02 | PFS03 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 9.81±2.97 | 9.49±3.20 | 9.52±2.78 | 9.10±2.52. |

| T2-5 | 5.05±0.97a | 5.20±1.38a | 5.06±1.23b | 5.60±1.24a |

| M1 | 12.63±1.94 | 12.76±2.28 | 12.45±1.57 | 12.95±1.49 |

| M2 | 17.12±2.37 | 15.63±1.39 | 15.64±1.51 | 16.45±1.47 |

| M3 | 17.20±2.13 | 16.35±1.90 | 16.04±1.54 | 16.82±2.40 |

| M4 | 15.98±4.12a | 14.99±4.04a | 14.41±2.56b | 14.19±2.83b |

| M5 | 9.55±3.39 | 9.04±3.43 | 8.75±2.38 | 8.41±2.40 |

| MF | 6.22±1.53a | 6.76±1.15b | 6.01±1.55a | 6.12±1.50a |

| MH | 16.22±2.14 | 15.95±2.46 | 15.89±1.81 | 16.58±2.46 |

| LH | 16.51±2.12a | 14.93±1.17b | 14.95±1.27b | 15.48±1.68b |

| F | 68.647*** | 57.433*** | 99.135*** | 92.200*** |

***p < 0.001, a, b: means with the same letters are not significantly different from Tukey's test.

As shown in Table 8, the plantar pressure results indicate that, during walking, pressure tended to concentrate in the meta and heel regions. The maximum plantar force values of S1 recorded in the force diagrams were 36.9 N/cm2 for BF, 34.1 N/cm2 for PFS01, 32.7 N/cm2 for PFS02, and 34.6 N/cm2 for PFS03. And the maximum plantar force values for S1 measured in the force diagrams were 38.8 N/cm2 for BF, 38.2 N/cm2 for PFS01, 38.1 N/cm2 for PFS02, and 39.1 N/cm2 for PFS03. These results suggested that wearing plantar fasciitis socks can help reduce plantar pressure during walking compared to barefoot walking. Moreover, the plantar force diagrams divided into 10 zones showed an increase in the contact area in the medial forefoot region when wearing socks compared to barefoot. An increased contact area between the sole and the ground implies better pressure distribution and enhanced gait stability [10,11].

Regarding peak pressure, in most zones, a reduction in peak pressure was observed when wearing the socks compared to the barefoot condition. Especially, PFS02 showed the best decreasing tendency in high-pressure zones such as the meta and heel. Moreover, all conditions showed statistically significant differences. In the M3, MH, and LH zones, the peak pressure values for PFS02 were 16.04 ± 1.54 N/cm2, 15.89 ± 1.81 N/cm2, and 14.95 ± 1.27 N/cm2, respectively. These values represented a reduction of approximately 2.03−9.45% compared to the barefoot condition, which showed 17.20 ± 2.13 N/cm2, 16.22 ± 2.14 N/cm2, and 16.51 ± 2.12 N/cm2, respectively. As confirmed in the thickness comparison in Section 3.3, the meta zone thickness for PFS01–03 samples ranged from 1.74 to 1.85 mm. In the case of PFS02, the toe zone had the greatest thickness at 1.71 ± 0.00 mm, which is likely associated with enhanced pressure dispersion. The heel zone thicknesses for PFS01–03 were measured at 1.85 ± 0.21 mm, 1.87 ± 0.00 mm, and 2.23 ± 0.06 mm, respectively. Compared with previous studies [12], where sports socks had heel thicknesses of 1.14 mm, 1.67 mm, and 2.07 mm, these values were generally greater. Furthermore, while the peak pressure in the MH and LH zones of sports socks in prior studies ranged from approximately 13−14 N/cm2 and 15−17 N/cm2, respectively, PFS01-03 showed peak pressures of 13.54−14.26 N/cm2 for MH and 12.65−13.79 N/cm2 for LH, confirming the effectiveness of these socks in reducing plantar pressure. Furthermore, a greater reduction in plantar pressure was observed in the HL zone compared to the HM zone. In particular, PFS01 and PFS02 showed lower values than PFS03. As confirmed in Section 3.1 and 3.2, this result can be attributed to the influence of the part and knit structures. In the cases of PFS01 and PFS02, each structure in the meta region differed, contributing to foot stabilization. For FPS01 and FPS02, the arch side and lateral midfoot part of the meta area of t he sole were segmented and composed. Specifically, the M3 part, composed of plain/jacquard structures with thicknesses of 2.94 ± 0.02 mm and 2.92 ± 0.11 mm, respectively, appeared to support the arch, thereby reducing and distributing plantar pressure. On the other hand, in the case of FPS03, it was segmented into 13 most parts, but in the meta area of t he sole, the arch and lateral midfoot were simply composed of the same structure as M1-M3. Therefore, it is thought that the pressure was not reduced compared to FPS01 and FPS02 when worn. Furthermore, the results of Tukey HSD post-hoc analysis confirmed significant differences between each sample in the T2-5, M4, MF, and LH zones (p < 0.05), and in particular, PFS02 showed statistically significantly lower peak pressure than most comparison groups. These results are interpreted as reflecting the structural design of PFS02 to effectively alleviate plantar pressure in the main area where the plantar fascia load is concentrated.

4. Conclusion

This study aimed to comparatively analyze the knitting structure, thickness, and stitch count across various sections of three types of plantar fasciitis socks, and to identify the most suitable knit design through plantar pressure analysis after wear.

As analyzed results of plantar faciitis socks, the structural and thickness analysis of plantar fasciitis socks revealed intentional variations in segmentation, particularly in the metatarsal and ankle regions, to optimize foot support, pressure distribution, and joint stabilization. In terms of structure analysis, PFS01 featured a relatively simple knit structure with moderate stitch densities. PFS02 demonstrated the most effective performance and incorporated targeted compression zones using rib and jacquard knits with high stitch density, especially in the ankle region, and exhibited the greatest localized thickness (3.07 mm at A1). PFS03 demonstrated heel cushioning with H1 and H2 measuring 2.27 ± 0.07 mm and 2.19 ± 0.09 mm respectively. All three socks concentrated thickness in the ankle and heel areas, indicating different design focuses for plantar fasciitis relief—PFS02 on ankle stability, PFS03 on shock absorption, and PFS01 on balanced support. Most importantly, plantar pressure analysis revealed that PFS02 achieved the greatest reduction in peak pressure values in critical zones (M3, MH, LH) and provided improved contact area, indicating more effective pressure dispersion and enhanced gait stability.

Thus, PFS02 was found to have the most suitable knit structure and design for plantar fasciitis relief and effective pressure reduction in high-stress regions. In future research, we aim to design socks specifically for individuals with plantar fasciitis based on the data from this study and conduct plantar pressure analysis.

References

- 1 J. Thing, M. Maruthappu, and J. Rogers, "Diagnosis and Management of Plantar Fasciitis in Primary Care" , Br. J. Gen. Pract., 2012, 62, 443-444.custom:[[[-]]]

- 2 C. J. Pearce, D. Seow, and B. P. Lau, "Correlation between Gastrocnemius Tightness and Heel Pain Severity in Plantar Fasciitis" , Foot Ankle Int., 2021, 42, 76-82.custom:[[[-]]]

- 3 J. L. Glazer, " An Approach to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis" , Phys. Sportsmed., 2009, 37, 74-79.custom:[[[-]]]

- 4 D. L. Riddle, M. Pulisic, P. Pidcoe, and R. E. Johnson, "Risk Factors for Plantar Fasciitis: A Matched Case-control Study" , J. Bone Joint Surg. Am., 2003, 85, 872-877.custom:[[[-]]]

- 5 J. Orchard, "Plantar Fasciitis" , BMJ, 2012, 345, e6603.custom:[[[-]]]

- 6 P . F . Davis, E. Severud, and D. E. Baxter, "Painful Heel Syndrome: Results of Nonoperative Treatment" , Foot Ankle Int., 1994, 15, 531-535.custom:[[[-]]]

- 7 G. Pfeffer, P. Bacchetti, J. Deland, A. Lewis, R. Anderson, W. Davis, R. Alvarez, J. Brodsky, P. Cooper, C. Frey, R. Herrick, M. Myerson, J. Sammarco, C. Janecki, S. Ross, M. Bowman, and R. Smith, "Comparison of Custom and Prefabricated Orthoses in the Initial Treatment of Proximal Plantar Fasciitis" , Foot Ankle Int., 1999, 20, 214-221.custom:[[[-]]]

- 8 L. D. Barry, A. N. Barry, and Y. Chen, " A Retrospective Study of Standing Gastrocnemius-soleus Stretching Versus Night Splinting in the Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis", J. Foot Ankle Res., 2002, 41, 221-227.custom:[[[-]]]

- 9 S. Ahmed, A. Barwick, P. Butterworth, and S. Nancarrow, "Footwear and Insole Design Features that Reduce Neuropathic Plantar Forefoot Ulcer Risk in People with Diabetes: A Systematic Literature Review" , J. Foot Ankle Res., 2020, 13, 30.custom:[[[-]]]

- 10 S. G. R. Khorasani, M. B. Cham, A. Sharifnezhad, H. Saeedi, and B. Farahmand, "Comparison of the Immediate Effects of Prefabricated Soft Medical Insoles and Custom-molded Rigid Medical Insoles on Plantar Pressure Distribution in Athletes with Flexible Flatfoot: A Prospective Study", Curr. Orthop. Pract., 2021, 32, 578-583.custom:[[[-]]]

- 11 Y .-P . Huang, H.-T . Peng, X. W ang, Z.-R. Chen, and C.-Y . Song, "The Arch Support Insoles Show Benefits to People with Flatfoot on Stance Time, Cadence, Plantar Pressure and Contact Area" , PLoS One, 2020, 15, e0237382.custom:[[[-]]]

- 12 R. T . Sadia, P . M. Hossain, I. Jung, and S. Lee, "Structure Analysis and Plantar Pressure Characteristics of Sports Socks" , T ext. Sci. Eng., 2025, 62, 33-43.custom:[[[-]]]

- 13 https://www.medcentral.com/pain/chronic/effective-protocol- management-plantar-fasciitis (Accessed May 27, 2025).custom:[[[https://www.medcentral.com/pain/chronic/effective-protocol-management-plantar-fasciitis(AccessedMay27,2025)]]]

- 14 https://os1st.com/products/fs4-plantar-fasciitis-sock?srsltid= AfmBOoq_IQkSvyexGc4FhJjVfNRF90QkUN25i661fRgmOO QzyZuJBS1l (Accessed May 19, 2025).custom:[[[https://os1st.com/products/fs4-plantar-fasciitis-sock?srsltid=AfmBOoq_IQkSvyexGc4FhJjVfNRF90QkUN25i661fRgmOOQzyZuJBS1l(AccessedMay19,2025)]]]

- 15 A. Perrier, N. Vuillerme, V. Luboz, M. Bucki, F. Cannard, B. Diot, D. Colin, D. Rin, J. P . Bourg, and Y . Payan, "Smart Diabetic Socks: Embedded Device for Diabetic Foot Prevention", IRBM, 2014, 35, 72-76.custom:[[[-]]]

- 16 G. Renganathan, Y. Kurita, S. Cukovic, and S. Das in "Foot Biomechanics with Emphasis on the Plantar Pressure Sensing: A Review" , in "Revolutions in Product Design and Healthcare" (M. Gupta, S. Das, and N. N. Q. Huynh Eds.), Springer, Singapore, 2022, pp.115-141.custom:[[[-]]]

- 17 P . Eizentals, A. Katashev, and A. Oks, " A Smart Socks System for Running Gait Analysis" , Proc. 7th Int. Conf. Sport Sci. Res. T echnol. Support (icSPORTS), Vienna, Austria, 2019, pp.47-54.custom:[[[-]]]

- 18 Z. Soltanzadeh, S. S. Najar, M. Haghpanahi, and M. R. Mohajeri- T ehrani, "Effect of Socks Structures on Plantar Dynamic Pressure Distribution" , Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H., 2016, 230, 1043-1050.custom:[[[-]]]

- 19 A. Martínez Nova, M. R. Cera Medrano, and P . V . Munuera, "Tratamiento Para La Fascitis Plantar Con Calcetines Biomecánicos. Resultados Preliminares de un Ensayo Clínico Aleatorio" , Rev. Esp. Podol., 2023, 34, 62-68.custom:[[[-]]]

- 20 M. B. Werd, E. L. Knight, and P. R. Langer (Eds.), " Athletic Footwear and Orthoses in Sports Medicine" , 2nd Ed., Springer, Cham, 2017, pp.19-34.custom:[[[-]]]

- 21 T. Tahmasbi and S. Mohammadi, "The Effect of Strassburg Sock Orthosis on Heel Pain and Quality of Life in Patients with Plantar Fasciitis Lesion", J. Res. Rehabil. Sci., 2019, 14, 325-331.custom:[[[-]]]

- 22 B. Baravarian, "Arch-supporting Sock" , US Patent 10,149,500 B2 (2018).custom:[[[-]]]

- 23 H. Jamshaid, R. K. Mishra, N. Ahamad, V. Chandan, M. Nadeem, V . Kolar, P . Jirku, M. Muller, T . Akshat, S. Nazari, and T . A. Ivanova, "Impact of Construction Parameters on Ergonomic and Thermo-physiological Comfort Performance of Knitted Occupational Compression Stocking Materials" , Heliyon, 2024, 10, e02735.custom:[[[-]]]

- 24 A. P . Ribeiro, F. Trombini-Souza, V . D. Tessutti, F. R. Lima, S. M. Joao, and I. C. Sacco, "The Effects of Plantar Fasciitis and Pain on Plantar Pressure Distribution of Recreational Runners" , Clin. Biomech., 2011, 26, 194-199.custom:[[[-]]]

- 25 A. N. Buck and S. P . Shultz, "Sockwear Influences Performance and Plantar Kinetics During Agility and Soccer Drills" , Int. J. Kinesiol. High. Educ., 2023, 8, 142−156.custom:[[[-]]]

- 26 D. N. T asron, T . J. Thurston, and M. J. Carre, "Frictional Behaviour of Running Sock Textiles Against Plantar Skin" , Procedia Eng., 2015, 112, 110-115.custom:[[[-]]]

- 27 E. Baussan, M. A. Bueno, R. M. Rossi, and S. Derler, " Analysis of Current Running Sock Structure with Regard to Blister Prevention " , Text. Res. J., 2013, 83, 836-848.custom:[[[-]]]

- 28 G. Semjonova, A. Davidovica, N. Kozlovskis, A. Okss, and A. Katashevs, "Smart Textile Sock System for Athletes Self- Correction During Functional Tasks: Formative Usability Evaluation " , Sensors, 2022, 22, 4779.custom:[[[-]]]

- 29 N. Sachez, B. F . Contreras, J. M. Garcia, R. D. Hernandez, and O. F. Aviles, "Plantar Fasciitis Treatments: A Review", Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res., 2018, 13, 13258-13267.custom:[[[-]]]

- 30 S. C. Wearing, J. E. Smeathers, M. Patrick, B. Y . Sullivan, R. U. Stephen, and D. Philip, "Plantar Fasciitis: Are Pain and Fascial Thickness Associated with Arch Shape and Loading?", Phys. Ther., 2007, 87, 1002-1008.custom:[[[-]]]