안젤린셀시야 , 민준영 , 김혜림

락을 활용한 박테리아 셀룰로스 섬유소재의 천연염색 특성 연구

Natural Dyeing Properties Using Lac for Bacterial Cellulose Fabrics

Angelin Selsiya J, Juneyoung Minn, and Hye Rim Kim

Abstract: This study investigates the coloration of bacterial cellulose (BC) using the animalderived natural dye lac with natural mordants such as pomegranate peel and grape seed. The effects of Al pre-treatment, dye concentration, dyeing solution pH, and dyeing temperature on the dyeability of BC were systematically examined. FT-IR analysis confirmed the formation of coordination complexes between lac and Al, demonstrating the presence of chemical bonding between them. FE-SEM images showed that some lac and Al were physically entrapped within the BC nanostructure. The application of bio-mordants was evaluated alongside metal mordants to assess color fastness properties. Samples treated with bio-mordants exhibited excellent fastness performance, with rubbing and dry-cleaning fastness rated between grades 4, 4-5, and 5. These findings demonstrate that the biomordant can be utilized as an environmentally sustainable and effective mordant.

Keywords: bacterial cellulose , natural dyeing , lac , bio mordant , pomegranate peel , grape seed

1. Introduction

The textile industry is a major source of environmental pollution and resource depletion, and consequently, sustainability has become a central focus within the field [1]. Among recent advancements in sustainable textile materials, bacterial cellulose (BC) has gained attention as a noteworthy development [2]. BC is a biogenic fabric synthesized by specific bacteria such as Acetobacter xylinum, Agrobacterium and Azotobacter [3]. Notable characteristics of BC include exceptional mechanical properties, high polymerization, significant crystallinity, and superior water holding capacity [4,5]. The dried BC closely resembles the appearance of natural leather and has been regarded as a promising leather substitute for the textile sector [6]. BC has the advantage of being cleanly and non-toxically produced, as it does not require the hazardous chemicals typically used in conventional leather processing [5].

However, research on the dyeing of BC has been limited to the use of either chemical dyes or plant-derived natural dyes [7−11]. To maintain the eco-friendly nature of BC, the application of natural dyeing is required. While plantderived natural dyes allow for sustainable dyeing of BC, their limited color fastness and susceptibility to fading over time have been noted as significant drawbacks [12]. In contrast, animal-based natural dyes provide a wide range of shades from earthy tones to vibrant hues, and certain dyes such as cochineal and lac exhibit superior light fastness compared to plant-derived dyes [12,13]. Among them, the coloration using lac has not been studied on BC. Thus, the aim of this study is to apply the animal-derived dye, lac to BC and to investigate the coloration of lac on BC.

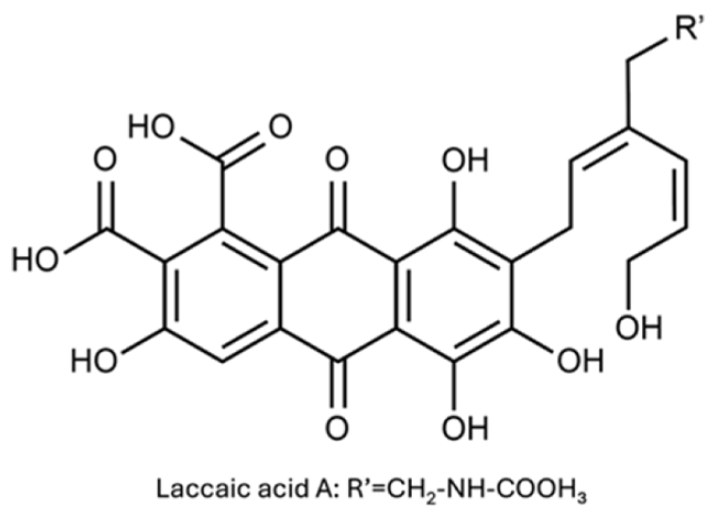

Lac dye is derived from stick lac secreted by the insect Laccifer lacca Kerr [14]. The dyeing capability of lac dye mainly results from anthraquinone-based compounds [14,15]. These compounds are a mixture of anthraquinone carboxylic acids, primarily consisting of laccaic acids A, B, C, D, and E, among which laccaic acid A accounts for more than 85% of the total composition [16]. Lac exhibits a red to purple hue due to the presence of laccaic acids, while also demonstrating high resistance to heat, light, and oxygen [17,18].

Mordanting is commonly employed in natural dyeing to improve fastness properties [19]. Nevertheless, metal mordants are associated with environmental issues, which has led to growing attention toward eco-friendly biomordants [9]. Thus, this study investigates the application of natural mordants in the context of BC produced under clean and nontoxic conditions. In this study, pomegranate peel (PP) and grape seed (GS) were selected as the tannin rich bio mordants [20,21]. PP and GS can be used as bio mordant due to their tannin contents, which can improve dye fixation between the dye and cellulose by forming hydrogen bonds [9].

Therefore, the aim of this study is to analyze the coloration characteristics of BC dyed with lac and bio-mordants including PP and GS under various dyeing conditions with a focus on developing an eco-friendly dyeing process. To achieve this, the color change under different dyeing condition such as Al-pretreatment application, dye concentration, dyeing solution pH, and dyeing temperature, are evaluated. Subsequently, FT-IR and FE-SEM are conducted to examine the dyeing behavior and chemical interaction between BC and lac. Finally, comparative analyses are conducted on the color changes and fastness properties resulting from the use of bio mordants and metal mordants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

A kombucha symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) was obtained from an online retailer (Joshua tree kombucha, USA). Peptone and yeast extract were acquired from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Glucose, sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98.0%), acetic acid ([TeX:] $$\mathrm{CH}_3 \mathrm{COOH},$$ 99.0%), hydrogen peroxide ([TeX:] $$\mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O}_2,$$ 34.5%), 1N sodium hydroxide solution (NaOH), potassium aluminum sulfate (AlK ([TeX:] $$\left.\mathrm{SO}_4\right)_2,$$ 99%), copper (II) sulfate ([TeX:] $$\mathrm{CuSO}_4 \quad 5 \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O},$$ 99%), iron (II) sulfate ([TeX:] $$\mathrm{FeSO}_4 \quad 7 \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O},$$ 98.0−102.0%) and perchloroethylene ([TeX:] $$\mathrm{C}_2 \mathrm{Cl}_4$$) were sourced from Duksan Pure Chemical (Ansan, South Korea). Lac powder were purchased from the Naju Natural Dyeing Cultural Foundation (Naju-si, South Korea). PP powder was purchased from Bixa Botanicals (Madhya Pradesh, India), and GS powder was obtained from Govinda Natur’s (Neustadt, Germany). The chemical structure of lacciac acid, which is the main pigment component in lac are shown in Table 1.

2.2. BC Production

BC was cultured using the approach of Han et al. [23] SCOBY was inoculated into Hestrin and Schramm medium (glucose 20 g/l, peptone 5 g/l, yeast extract 5 g/l) and incubated statically at [TeX:] $$272^{\circ} \mathrm{C}$$ for 7–10 days until BC attained a thickness of 1 cm. The pre-treatment of BC followed the procedure described in Han et al. [23] and Song et al. [24], which included boiling, swelling, bleaching, and neutralization steps. Swelling was carried out to expand the dense nanostructure of BC, thereby enabling the entrapment of dyes within the nanostructure, while bleaching was applied to allow objective color analysis of the applied dyes [23,24].

The resulting pre-treated dried BC is referred to as original BC (OBC), and its characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

| Sample | Weight (g/m2) | Thickness (mm) | Moisture region (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OBC | 103.0±22.5 | 0.32±0.07 | 9.60±0.48 |

2.3. Dyeing and Mordanting

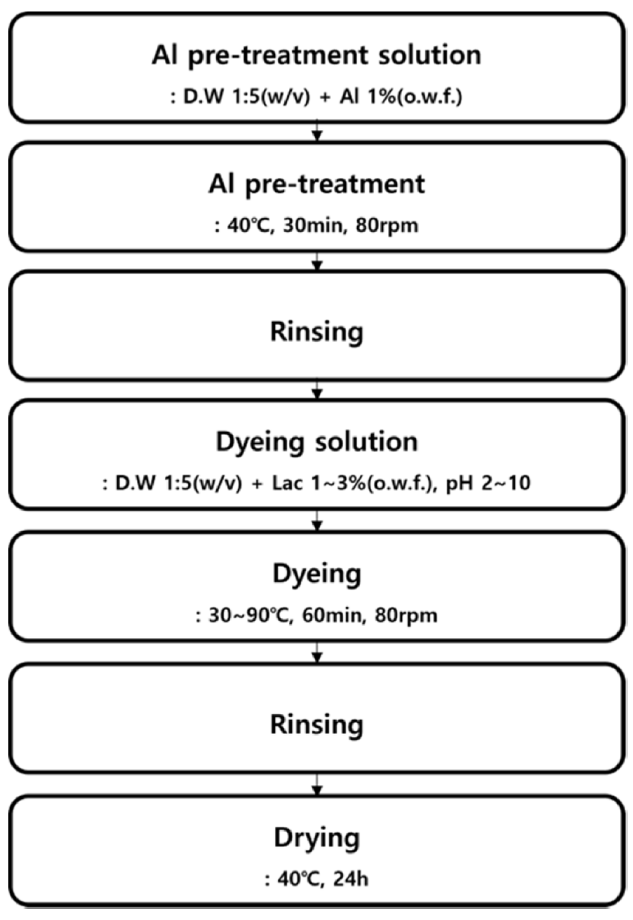

To evaluate the color changes under different dyeing conditions and to establish the dyeing parameters, dyeing was carried out as shown in Figure 1. Lac dyeing was conducted after an Al pre-treatment step. BC was pre-treated with 1% (o.w.f.) Al solution at [TeX:] $$40^{\circ} \mathrm{C}$$ for 30 min at 80 rpm. Dyeing was performed at a liquor ratio 1:5(w/v, of wet BC) with shaking 80rpm for 60min in a shaking water bath (BS2- 30; JEIO TECH Co., Daejeon, Korea). The dyeing condition were determined by varying the parameter such as Al pretreatment (present or absent), dye concentration (1~3% (o.w.f.)), solution pH (pH 2~10), and dyeing temperature [TeX:] $$\left(30 \sim 90^{\circ} \mathrm{C}\right) .$$

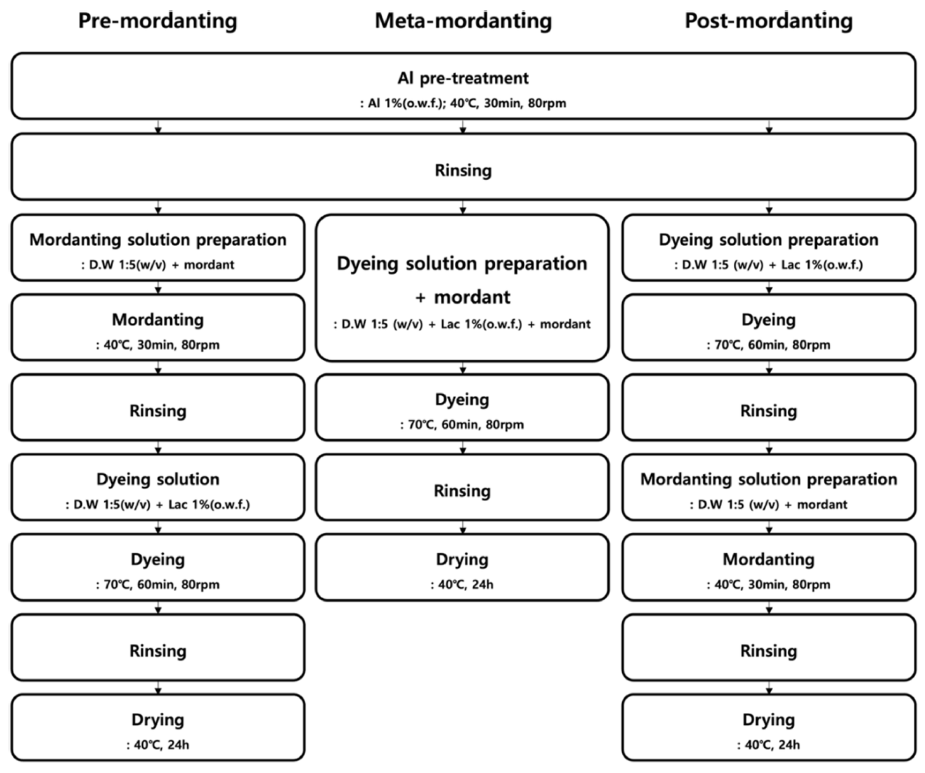

Mordanting of BC involved the use of PP 10% (o.w.f.), GS 10% (o.w.f.), Cu 2% (o.w.f.), and Fe 1% (o.w.f.) through pre-, meta-, and post-mordanting methods (Figure 2). Both premordanting and post-mordanting processes were conducted at [TeX:] $$40^{\circ} \mathrm{C}$$ for 30 min at 80 rpm. For meta-mordanting, mordants were added directly to the dye bath. After dyeing and mordanting steps, the samples were dried at [TeX:] $$40^{\circ} \mathrm{C}$$ for 24 hours in a drying oven (OF-22GW, Jeio Tech, Daejeon, South Korea).

2.4. Measurement of Dye Adsorption and Surface Color

The color values and color strength of the dyed BC were evaluated using a spectrophotometer (CCM, CM-2600d, Konica Minolta Sensing, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The color values with the CIELAB color system were expressed using, [TeX:] $$L^*, a^*, b^*$$ coordinates, and the hue (H), value (V), and chroma (C) were obtained using the Munsell colorimetric conversion method. The color strength (K/S) value was determined in accordance with the Kubelka-Munk equation. All photos of dyed BC were taken at 10 magnification, with the sample fixed at a distance of 10 cm.

2.5. Characterization

The dyeing solution was characterized by UV-vis absorption spectrophotometer (UV-1900i Plus, Shimadzu, Japan) in the range of 400−650 nm. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using D8 ADVANCE diffractometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) under range of f [TeX:] $$2 \theta=0^{\circ}-40^{\circ}$$ using Cu-Kα (λ = 1.5406 nm) radiation. The crystallinity (%) was calculated using Origin Pro software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). Fourier transform-infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy (Nicolet iS50, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was analyzed to investigate the chemical interaction between BC and lac. Transmittance mode was used with a total 32 scans and resolution of 4cm-1 at a range of 4,000 to 800 cm-1. Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) (SM-7600F; JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used to analysis the surface morphology of the samples. All samples were coated with Pt and measured with a magnification of ×15,000.

2.6. Color Fastness Testing

To evaluate the color fastness of the dyed BC, we analyzed rubbing, dry cleaning, and light fastness, which are relevant to its intended use as a leather alternative. The rubbing fastness test was performed on a CROCK METER (Sungshin Testing W.C Co., Korea) according to ISO 105-X12:2016 (Textile – test for color fastness – Part X12: Color fastness to rubbing). Dry cleaning fastness was tested using a drycleaning tester (Sungshin Testing M.C Co., Korea) following the ISO 105-D01:2010 (Textile test for color fastness – Part D01: Color fastness to dry cleaning using perchloroethylene solvent). Rubbing fastness and dry-cleaning fastness were measured using CCM following ISO 105-A04:1989 (Textiles- Tests for colour fastness Part A04: Method for instrumental assessment of the degree of staining of adjacent fabrics) and ISO 105-A05:1996 (Textiles-Tests for colour fastness Part A05: Instrumental assessment of change in colour for determination of grey scale rating) respectively. Light fastness was evaluated using a Xenon Arc Weather-Ometer (CI4000, ABNEXO Co., Korea) according to ISO 105- B02:2014 (Textiles-Test for colour fastness Part B02: Colour fastness to artificial light: Xenon arc fading lamp test) and evaluated according to the ISO 150-A02:1993 (Textiles-Tests for colour fastness Part A02: Grey scale for assessing change in colour).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dyeing Conditions of BC Dyed with Lac

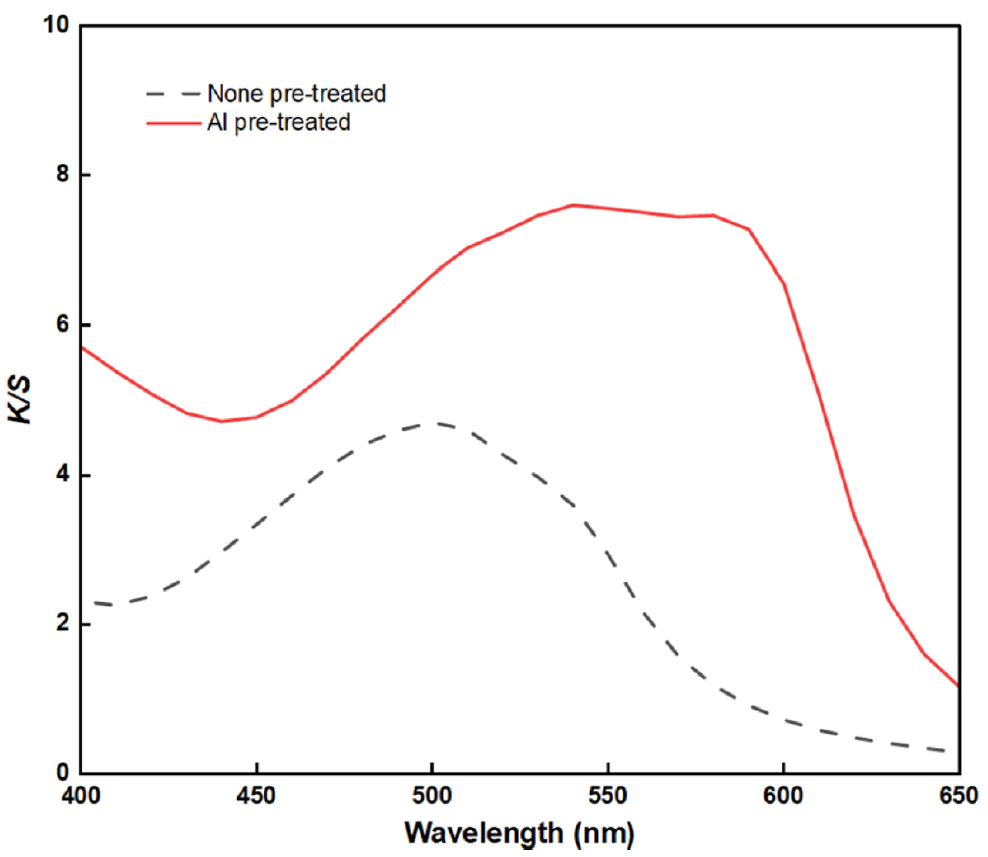

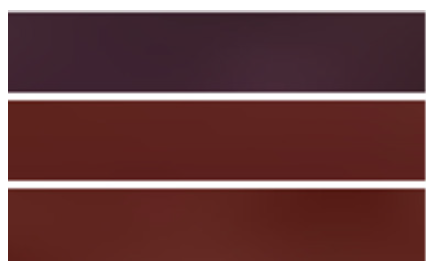

Effects of Al Pre-treatment on the BC Fabric: The color values and wavelength curves depending on Al pretreatment are shown in Table 3 and Figure 3. As shown in Table 3, without Al pre-treatment, the fabric exhibited a red (R) hue in the orange–red range, whereas when Al pretreatment was applied, a reddish-purple hue was observed. Moreover, as shown in Figure 3, the wavelength at which the highest K/S value is observed at 500 nm and shifted to 540 nm upon the application of Al pre-treatment. This was attributed to the effect of Al ions used in the pre-treatment, as the metal ions induced a bathochromic shift of laccaic acids A and B, leading to a shift to longer wavelengths and a consequent change in color [14]. In addition, the K/S value increased approximately 1.6 times up when Al pre-treatment was applied, which was confirmed that Al pre-treatment had significant effect on enhancing dye uptake. In general, due to the anthraquinone structure of lac, its affinity for cellulose is extremely low [25]. However, after applying Al, Al metal ion forms a coordinated complex with cellulose and laccaic acid anion because the trivalent cation of Al can interact simultaneously between cellulose and laccaic acid [26].

Table 3.

| Al pre-treatment | [TeX:] $$L^*$$ | [TeX:] $$a^*$$ | [TeX:] $$b^*$$ | H | V | C | [TeX:] $$\lambda_{\max}$$ | K/S | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None-pre-treated | 50.04 | 31.19 | 15.78 | 6.0R | 4.94 | 7.25 | 500 nm | 4.70 |  |

| Al pre-treated | 32.05 | 14.72 | -3.95 | 4.8RP | 3.13 | 3.52 | 540 nm | 7.60 |

Thus, to enhance the dye uptake during lac dyeing, Al pretreatment was applied as the lac dyeing condition.

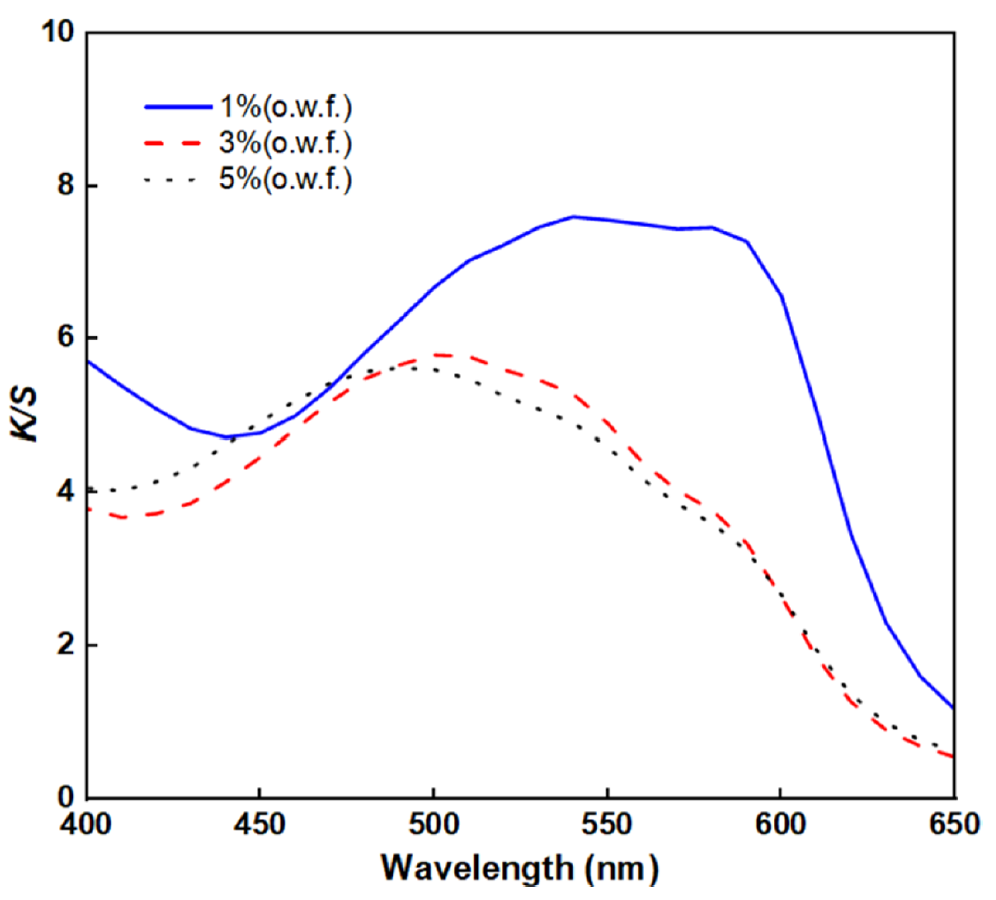

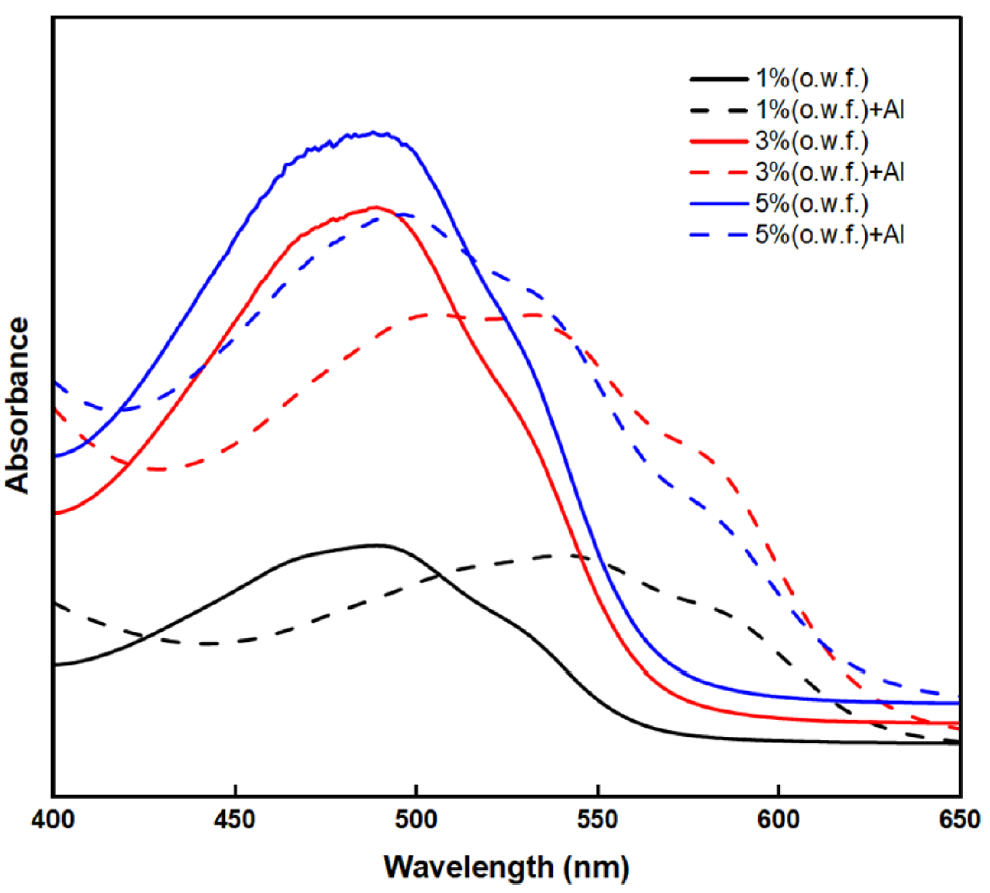

Effects of the Dye Concentration on the BC Fabric: The color values and wavelength curves depending on the dye concentration are shown in Table 4 and Figure 4. As shown in Figure 4, when the dye concentration exceeded 1% (o.w.f.), the wavelength corresponding to the maximum K/S value shifted to a lower wavelength, and the color changed from a reddish purple (RP) to red (R) hue. The bathochromic shift was attributed to the Al which was used in the pretreatment process [14]. Figure 5 describes the UV spectra of 1~5%(o.w.f.) lac dyeing solution with and without 1% Al. In Figure 5, the UV spectra of the dyeing solution without Al addition exhibit only changes in absorbance intensity depending on the concentration, without any detectable wavelength shift. However, when 1%(o.w.f.) Al was added, the spectral curve shifted toward a longer wavelength, and this shift was found to be more pronounced at lower dye concentrations. According to the result of Tanikawa et al. [27], increasing Al concentration promotes the complex formation with anthocyanins which leads the color shift from red to purplish red hue. A comparable trend is observed in lac as well, where laccaic acid forms a purple complex with Al [14]. When the lac concentration increases, the fixed amount of Al becomes insufficient to coordinate with all dye molecules. Consequently, the proportion of uncomplexed lac increases, resulting in a relatively reduced bathochromic shift. Moreover, as shown in Table 4, the highest K/S value was found at 1%(o.w.f.) which was the lowest dye concentration.

Table 4.

| Lac concentration (% o.w.f.) | [TeX:] $$L^*$$ | [TeX:] $$a^*$$ | [TeX:] $$b^*$$ | H | V | C | [TeX:] $$\lambda_{\max}$$ | K/S | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32.05 | 14.72 | -3.95 | 4.8RP | 3.13 | 3.52 | 540 nm | 7.60 |  |

| 3 | 39.69 | 23.62 | 5.88 | 1.93R | 3.90 | 5.45 | 500 nm | 5.79 | |

| 5 | 39.86 | 20.88 | 8.13 | 4.06R | 3.92 | 4.79 | 490 nm | 5.62 |

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Therefore, 1% (o.w.f.) was chosen as the optimal lac dyeing condition for BC, yielding the deepest shade with reduced dye consumption and improved cost efficiency.

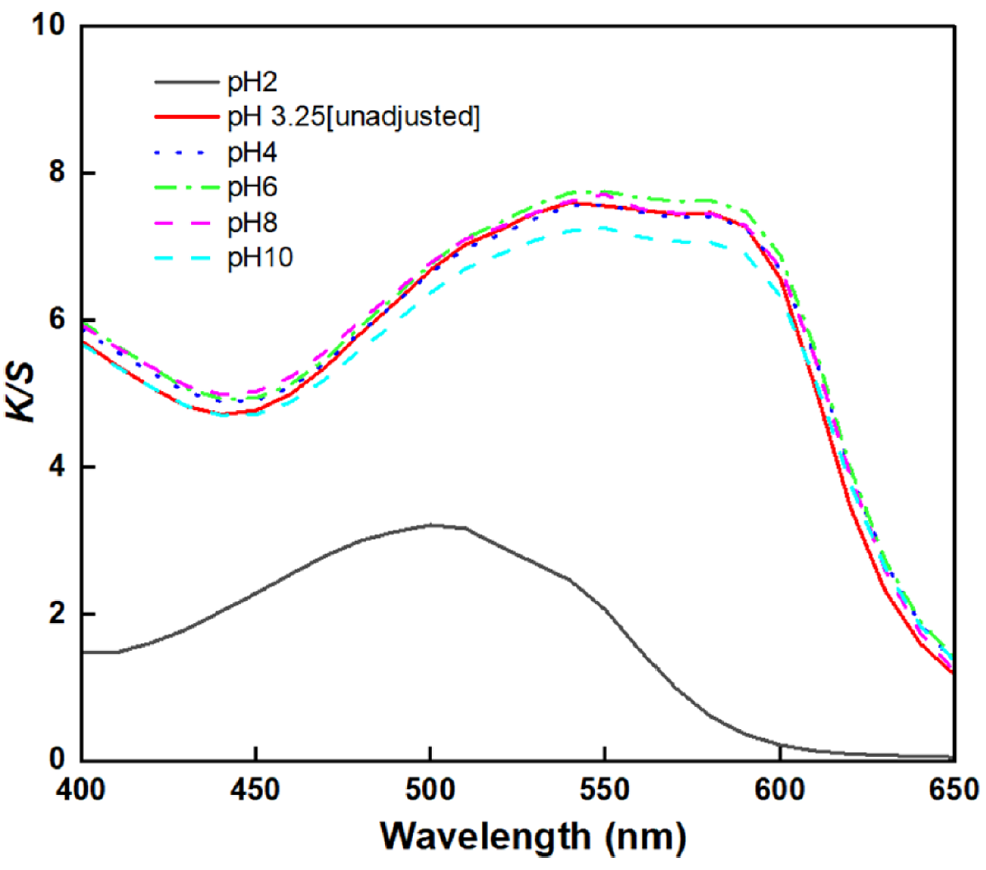

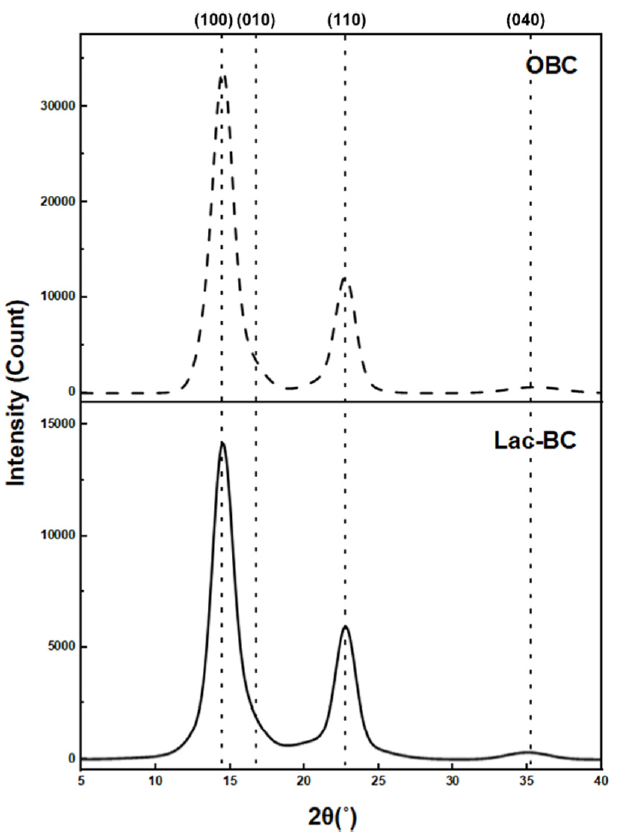

Effects of the Dyeing Solution pH on the BC Fabric: The color values and wavelength curves depending on the dyeing solution pH are shown in Table 5 and Figure 6. As shown in Figure 6 and Table 5, at pH 3.25 to 10, the color of lac dyed BC exhibited a reddish-purple (RP) hue, with the wavelength corresponding to the maximum K/S value appearing in the range of 540–550 nm. At pH 2, the maximum K/S value was observed at 500 nm, with an orange coloration. The reddish-purple color observed at pH 3.25 to 10 was attributed to the influence of aluminum pretreatment, which was described in section ‘Effects of Al Pre-treatment on the BC Fabric’, aluminum and lac dye react to form a coordinated complex, inducing a bathochromic shift and resulting in a color change from orange to a purple hue [14,25]. However, at pH 2, the dyed BC exhibits an orange tone with reduced dye uptake. This was attributed to the rate of aluminum complex formation reaches a minimum below pH 3, making it difficult for aluminum to form metal complexes with lac at such a low pH of 2 [28]. In general, during dyeing of cellulose fibers such as cotton, strong acidic conditions are not preferred, even if they result in high dye uptake, because cellulose fibers can undergo acid hydrolysis under low pH, leading to damage of the material [29]. In contrast, BC is produced by acetic acid bacteria through oxidative synthesis in an acidic culture medium of approximately pH 3, exhibiting high tolerance to acidic conditions [11]. Moreover, BC is presumed to exhibit high acid resistance due to its high crystallinity. The crystalline regions generally exhibit high resistance to acid, whereas the amorphous or disordered portions of BC are more susceptible to acid hydrolysis [30]. The XRD results presented in Figure 7 and Table 6 indicate that the OBC used in this study possesses a high crystallinity of 86.05%, which is presumed to confer strong resistance to acid [30]. In addition, as shown in the XRD spectra of OBC, the diffraction plane (100), (010), (110), and (040) plane corresponding to cellulose I appeared at [TeX:] $$2 \theta=14.5^{\circ}$$, 16.8, [TeX:] $$22.6^{\circ}, 34.0^{\circ}$$ respectively [31]. These peaks were also observed in the XRD pattern of BC dyed with lac which were dyed under pH 3.25 [Unadjusted] condition. In addition, after dyeing the crystallinity was 84.37% which had no significant difference with OBC. Thus, this observation indicates that the crystalline structure of cellulose remains intact at pH 3.25 and that its crystallinity is not affected. Hence, BC is considered to possess high acid resistance due to its high degree of crystallinity, and the pH 3.25 dyeing condition is presumed not to cause structural damage to BC. Consequently, BC can be dyed in strongly acidic environments without substrate damage [11].

Table 5.

| pH | [TeX:] $$L^*$$ | [TeX:] $$a^*$$ | [TeX:] $$b^*$$ | H | V | C | [TeX:] $$\lambda_{\max}$$ | K/S | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 59.10 | 39.61 | 20.13 | 5.5R | 5.85 | 9.69 | 500 | 3.20 |  |

| 3.25 [Unadjusted] | 35.05 | 14.71 | -3.94 | 4.8RP | 3.12 | 3.51 | 540 | 7.59 | |

| 4 | 31.97 | 13.60 | -3.81 | 4.3RP | 3.11 | 3.24 | 550 | 7.57 | |

| 6 | 31.67 | 13.54 | -4.13 | 3.8RP | 3.09 | 3.22 | 550 | 7.74 | |

| 8 | 31.71 | 13.42 | -4.33 | 3.9RP | 3.09 | 3.20 | 550 | 7.70 | |

| 10 | 32.53 | 13.36 | -3.91 | 3.9RP | 3.17 | 3.20 | 550 | 7.25 |

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Table 6.

| Sample | Crystallinity (%) |

|---|---|

| OBC | 86.05 |

| Lac-BC | 84.37 |

Thus, the dye solution pH was set to an economical, unadjusted pH of 3.25 for lac dyeing, as this condition provided the best dyeability without the need for additional pH adjustment.

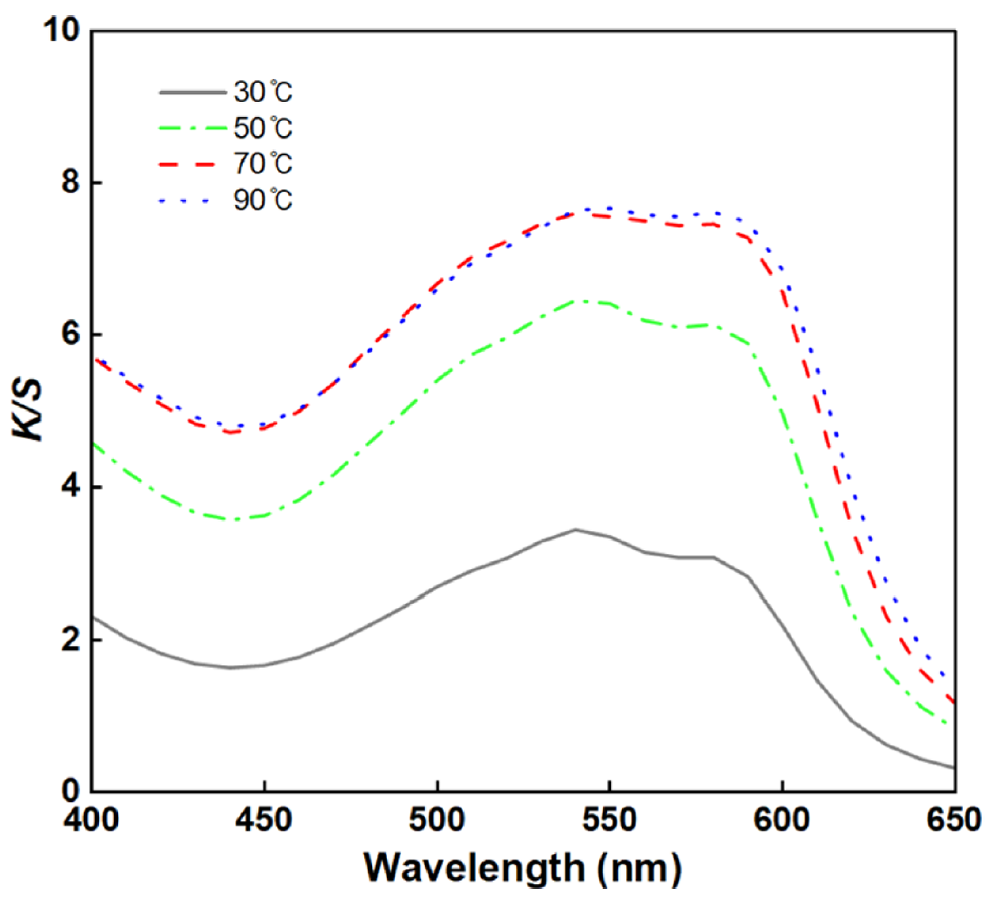

Effects of the Dyeing Temperature on the BC Fabric: The color values and wavelength curves depending on the dyeing solution pH are shown in Table 7 and Figure 8. As presented in Table 7, the K/S values increased progressively as the dyeing temperature rose from [TeX:] $$30^{\circ} \mathrm{C} \text { to } 90^{\circ} \mathrm{C},$$ with K/S values at [TeX:] $$70^{\circ} \mathrm{C} \text { and } 90^{\circ} \mathrm{C}$$ being comparable. The enhanced dye uptake at higher temperatures is attributed to increased molecular mobility and improved diffusion of dye molecules into BC, which suggests that dyeing equilibrium was achieved at [TeX:] $$70^{\circ} \mathrm{C}$$ [32].

Table 7.

| Temperature ([TeX:] $$^{\circ} \mathrm{C}$$) | [TeX:] $$L^*$$ | [TeX:] $$a^*$$ | [TeX:] $$b^*$$ | H | V | C | [TeX:] $$\lambda_{\max}$$ | K/S | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 46.04 | 21.96 | -6.56 | 3.3RP | 4.47 | 6.00 | 540 nm | 3.44 | |

| 50 | 35.49 | 18.33 | -4.99 | 3.6RP | 3.46 | 4.60 | 540 nm | 6.45 | |

| 70 | 32.05 | 14.72 | -3.95 | 4.8RP | 3.13 | 3.52 | 540 nm | 7.60 | |

| 90 | 31.94 | 13.95 | -4.34 | 4.6RP | 3.12 | 3.38 | 550 nm | 7.68 |

Figure 8.

Thus, [TeX:] $$70^{\circ} \mathrm{C}$$ was selected as the dyeing temperature for lac dyeing of BC.

Based on the above results, the dyeing condition were determined to apply Al pre-treatment, dye concentration 1%(o.w.f.), unadjusted dyeing solution pH (3.25), and a dyeing temperature [TeX:] $$70^{\circ} \mathrm{C}$$ for lac dyed BC.

3.2. FT-IR Analysis

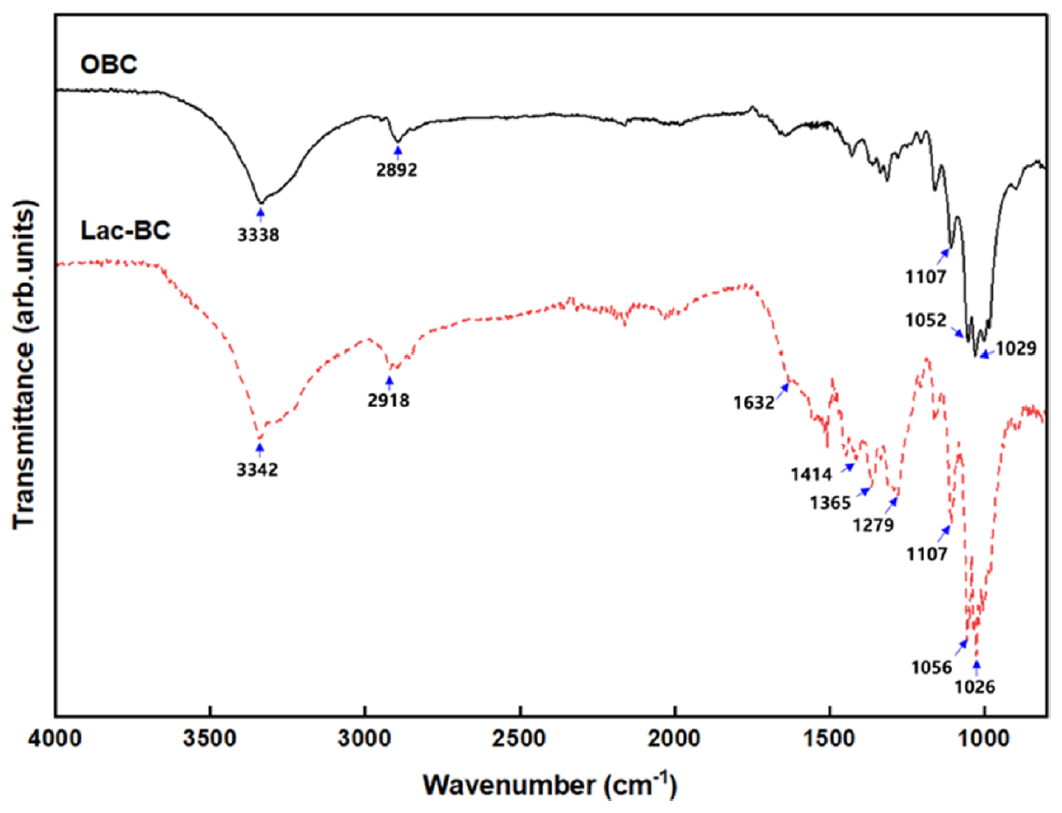

The FT-IR spectra of OBC and lac dyed BC are shown in Figure 9 and the characteristic peaks are listed in Table 8. The absorption peaks of OBC and lac dyed BC appear near 3330−3350, 2890−2920, 1107, 1052, and 1029 cm-1 corresponding to the -OH stretching, C-H stretching, ring asymmetric stretching vibrations, and C-O stretching in cellulose, respectively [31, 33−34]. After dyeing, the peak near 3330−3350 and 1107 cm-1 was deeper and several characteristic peaks of lac was observed. The change in the intensity of the –OH stretching band is attributed to the phenolic –OH or the –OH group of the carboxylic acid in lac, indicating their involvement in the binding interaction [35]. The peak at 1107 cm-1 was more intense, corresponding to =C–H bonds, which are related to the components of lac and are interpreted as resulting from the interaction between BC and lac [36]. Moreover, the absorption peak observed at 1632 cm-1 corresponds to C=O stretching vibration, which was attributed to the formation of a metal chelate complex [37]. This peak arises when the hydrogen bond with OH group in hydroxyanthraquinone is replaced by a metal ion, allowing coordination between the metal ion and the carbonyl group [37]. These results indicates that both lac and BC formed metal chelates as a result of the Al pre-treatment [37]. The peaks at 1414, 1365, and 1279 cm-1 were assigned to the -OH in‐plane bending of carboxylic acid dimers, deformation mode of methylene group, and C-O stretching vibration of lac, respectively [38,39].

Figure 9.

Table 8.

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Peak assignment | |

|---|---|---|

| OBC | Lac-BC | |

| 3338 | 3342 | -OH stretching [31] |

| 2892 | 2918 | C-H stretching [31] |

| - | 1632 | C=O stretching vibration [37] |

| - | 1414 | ‐OH in‐plane bending of carboxylic acid dimers [39] |

| - | 1365 | Deformation mode of methylene group [35] |

| - | 1279 | C–O stretching vibration [38] =C-H bond → lac [36] |

| 1107 | 1107 | Ring asymmetric stretching vibrations → cellulose [33] |

| 1052 | 1056 | C-O stretching [34] |

| 1029 | 1026 | C-O stretching [34] |

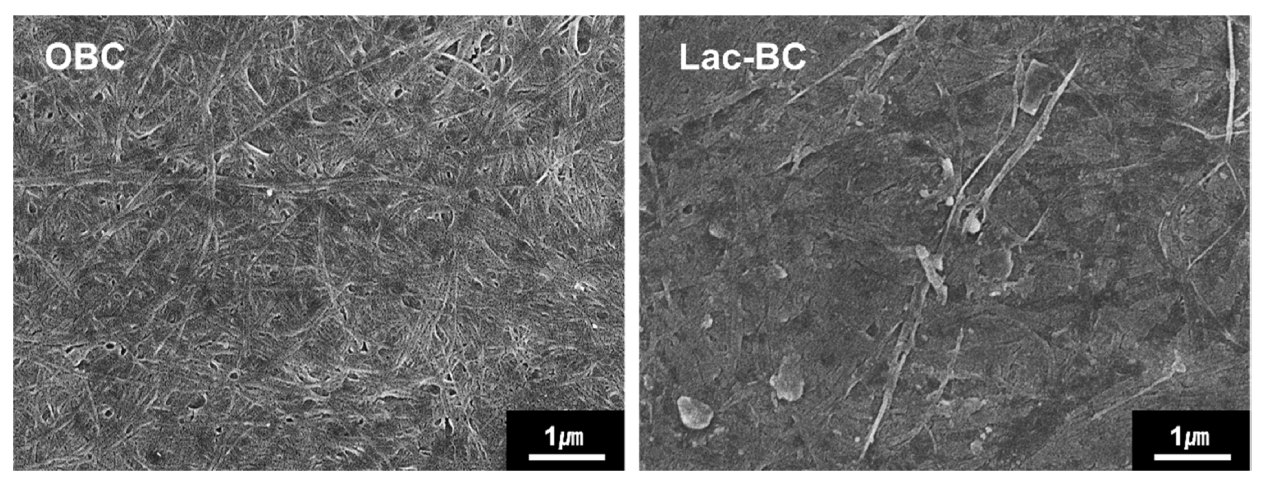

3.3. FE-SEM Analysis

Figure 10 shows the FE-SEM image of OBC and lac dyed BC. As shown in Figure 10(a), OBC shows the fine cellulose nanofibrils and porous structures [31]. In the case of lac dyed BC the pores observed in the OBC were mostly filled, resulting in a smooth, coated surface. Moreover, fine platelet- shaped particles and small spherical particles were observed on the surface and within the nanofibers of BC, which were identified as lac and Al, respectively [17]. Thus, the surface morphology analysis confirmed that lac and Al were entrapped within the BC matrix.

Figure 10.

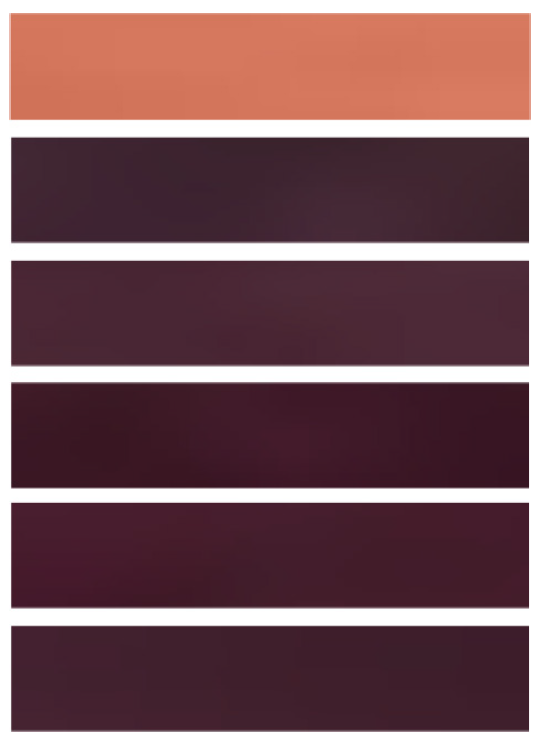

3.4. Mordanting of BC

Table 9 present the K/S value and colorimetric values of lac dyed BC using various mordants (PP, GS, Cu, Fe) applied via different mordanting methods (pre, meta, post). After mordanting, the surface color of lac dyed BCs exhibited a range of hues, including red (R), reddish purple (RP), purple (P), purplish blue (PB), and yellow (Y). Pre-mordanting shown the highest K/S value regardless of applied mordants. Application of meta-mordanting results in reduced dye uptake, and dyeing was found to be extremely limited when Cu or Fe was used as the mordants. This might be attributed to the increased molecules size caused by the pre-formation of dye and mordant complexes [40]. As previously discussed, the dyeing of BC with lac occurs through two behaviors: (1) physical entrapment; (2) formation of coordination complex between lac, Al, and BC. However, in meta-mordanting, it is presumed that the dye and mordant form a complex prior to interaction with BC, which may increase the molecular size that exceeds the entrapment capacity of BC pores and thus possibly reduce dye adsorption [40,41].

Table 9.

| Mordanting method | Mordant | [TeX:] $$L^*$$ | [TeX:] $$a^*$$ | [TeX:] $$b^*$$ | H | V | C | [TeX:] $$\lambda_{\max}$$ | K/S | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OBC | − | 91.04 | -0.35 | 4.37 | 5.1Y | 9.01 | 0.5 | 400 | 0.15 |  |

| None-mordanted | − | 32.06 | 14.71 | -3.94 | 4.8RP | 3.12 | 3.51 | 540 | 7.59 |  |

| Pre-mordanting | PP | 41.54 | 30.95 | 20.12 | 8.0R | 4.12 | 7.22 | 500 | 8.82 |  |

| GS | 39.11 | 25.18 | 11.62 | 5.7R | 3.87 | 5.57 | 500 | 7.90 | ||

| Cu | 23.07 | 5.26 | -0.34 | 8.8RP | 2.25 | 0.99 | 510 | 13.74 | ||

| Fe | 22.56 | 0.18 | -1.04 | 5.1PB | 2.18 | 0.20 | 640 | 12.88 | ||

| Meta-mordanting | PP | 43.78 | 29.24 | 18.52 | 7.9R | 4.34 | 6.77 | 500 | 7.14 |  |

| GS | 42.18 | 31.19 | 2.88 | 9.0RP | 4.14 | 7.44 | 520 | 5.59 | ||

| Cu | 80.55 | -0.97 | -2.55 | 4.3PB | 7.90 | 1.10 | 690 | 0.33 | ||

| Fe | 65.23 | 1.00 | 2.98 | 0.9Y | 6.37 | 0.50 | 400 | 1.11 | ||

| Post-mordanting | PP | 33.09 | 19.91 | 4.11 | 0.8R | 3.25 | 4.59 | 540 | 8.11 |  |

| GS | 32.79 | 15.19 | -3.26 | 4.8RP | 3.20 | 3.46 | 530 | 7.35 | ||

| Cu | 31.76 | 5.95 | -6.13 | 7.1P | 3.08 | 1.73 | 580 | 7.15 | ||

| Fe | 30.60 | 1.99 | -5.50 | 0.2P | 2.96 | 1.10 | 590 | 7.39 |

Hence, pre-mordanting method was selected for lac dyed BC due to the highest dye uptake.

3.5. Color Fastness Evaluation

Since BC was proposed as a leather substitute, this study evaluated rubbing, dry-cleaning, and light fastness of lac dyed BC and are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

| Mordanting method | Rubbing fastness | Dry cleaning fastness | Light fastness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mordant | Staining | Color change | Staining | Color change | Color change | ||

| Cotton | Wool | ||||||

| None | − | 4-5 | 4-5 | 4-5 | 4-5 | 4-5 | 4-5 |

| Pre-mordanting | PP | 4-5 | 5 | 4-5 | 5 | 4-5 | 4-5 |

| GS | 4 | 4 | 4-5 | 5 | 5 | 4-5 | |

| Cu | 4-5 | 5 | 4-5 | 4-5 | 4-5 | 4-5 | |

| Fe | 3-4 | 3-4 | 4 | 4-5 | 5 | 4-5 | |

1: Very Poor, 2: Poor, 3: Fair, 4: Good, 5: Very Good.

Apart from the lac–Fe sample, all other samples showed high fastness grades of 4, 4–5, and 5. Mordanting with PP maintained or improved the fastness value, whereas mordanting with GS slightly decreased rubbing fastness but enhanced dry cleaning fastness. This enhanced fastness value was attributed to tannin constituents in PP and GS, which interact with dye molecules to form stable complexes on the BC surface [42]. For light fastness, all samples achieved ratings of grade 4–5 regardless of the mordant applied. The high light fastness was attributed to the anthraquinone-based chromophores of lac, which have strong resistance to photooxidation under ultraviolet and visible light, resulting in significant photostability and durability [43]. In addition, since there was no significant difference in fastness compared to metal mordants, bio mordants can effectively substitute for them while maintaining the eco-friendly properties of BC [9].

4. Conclusion

In this study, lac dyeing conditions for BC were established, and the color properties and fastness characteristics were analyzed through the application of biomordants such as PP and GS.

First, the color change under different dyeing condition such as Al-pretreatment application, dye concentration, dyeing solution pH, and dyeing temperature, were evaluated. The selected dyeing conditions, based on the K/S value, were as follows: apply Al pre-treatment, dye concentration 1% (o.w.f.), unadjusted dyeing solution pH (3.25), and a dyeing temperature [TeX:] $$70^{\circ} \mathrm{C}$$

Secondly, FT-IR analysis confirmed the formation of coordination complexes between lac and Al, demonstrating the presence of chemical bonding between them. FE-SEM analysis revealed that some lac and Al were entrapped within the BC matrix.

Thirdly, after mordanting, the surface color of lac dyed BCs exhibited a range of hues, including red (R), reddish purple (RP), purple (P), purplish blue (PB), and yellow (Y). The pre-mordanting method was confirmed to yield the highest dye uptake.

Lastly, both PP and GS bio mordants demonstrated rubbing and dry cleaning fastness comparable to metal mordants, achieving grades of 4, 4-5, and 5. Regardless of mordanting, all samples exhibited light fastness of grade 4– 5, confirming the inherently excellent light resistance of the lac dye.

Therefore, based on the results of this study, the dyeing behavior of the animal-derived dyes, lac and BC, was elucidated, and dyeing conditions were established. Furthermore, the effectiveness of bio-mordants was verified, contributing to the development of an eco-friendly dyeing process utilizing BC. However, this study is limited in that Al was used as a pretreatment agent, which raises concerns regarding environmental sustainability. Hence, further research is needed to explore eco-friendly alternatives that can replace Al in the pretreatment process. In addition, although polychromatic dyes were employed to expand the color range of BC in this study, the dyed BC exhibited a broad absorption range, resulting in relatively low color selectivity. Future studies should focus on identifying dyeing strategies or modifying dye-fiber interactions to enhance the chromatic purity and color vividness of individual hues.

Acknowledgement: English language editing was provided by HARRISCO (http://en.harrisco.net).

References

- 1 K. Fletcher, "Sustainable Fashion and T extiles: Design Journeys" , Routledge, London, 2013, p.4.custom:[[[-]]]

- 2 U. Römling and M. Y. Galperin, "Bacterial Cellulose Biosynthesis: Diversity of Operons, Subunits, Products, and Functions" , Trends Microbiol, 2015, 23, 545-557.custom:[[[-]]]

- 3 Y. Huang, C. Zhu, J. Yang, Y. Nie, C. Chen, and D. Sun, "Recent Advances in Bacterial Cellulose" , Cellulose, 2014, 21, 1-30.custom:[[[-]]]

- 4 S. M. Choi, K. M. Rao, S. M. Zo, E. J. Shin, and S. S. Han, "Bacterial Cellulose and Its Applications" , Polymers, 2022, 14, 1080.custom:[[[-]]]

- 5 H. Kim, J. E. Song, and H. R. Kim, "Comparative Study on the Physical Entrapment of Soy and Mushroom Proteins on the Durability of Bacterial Cellulose Bio-leather" , Cellulose, 2021, 28, 3183-3200.custom:[[[-]]]

- 6 S. M. Yim, J. E. Song, and H. R. Kim, "Production and Characterization of Bacterial Cellulose Fabrics by Nitrogen Sources of T ea and Carbon Sources of Sugar" , Process Biochem, 2017, 59, 26-36.custom:[[[-]]]

- 7 Y. Tang, Y. Xue, J. Yuan, and J. Xu, "Research and Application of Bacterial Cellulose as a Fashionable Biomaterial in Dyeing and Printing" , Sustainability, 2025, 17, 7631.custom:[[[-]]]

- 8 A. F. S. Costa, J. D. P . de Amorim, F. C. G. Almeida, I. D. de Lima, S. C. de Paiva, M. A. V . Rocha, G. M. Vinhas, and L. A. Sarubbo, "Dyeing of Bacterial Cellulose Films Using Plant- based Natural Dyes" , Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2019, 121, 580- 587.custom:[[[-]]]

- 9 J. Minn, H. Kim, and H. R. Kim, "Assessing the Dyeing Properties of Bacterial Cellulose Using Plant-based Natural Dyes" , J. Korean Soc. Clothing Text., 2024, 48, 707-728.custom:[[[-]]]

- 10 E. Shim and H. R. Kim, "Coloration of Bacterial Cellulose Using In Situ and Ex Situ Methods", Text. Res. J., 2018, 89, 1297-1310.custom:[[[-]]]

- 11 Y. Hwang, H. Kim, and H. R. Kim, "Dyeing Properties of Bacterial Cellulose Fabric Using Gardenia Jasminoides, Green Tea, and Pomegranate Peel, and the Effects of Protein Pretreatment" , J. Korean Soc. Clothing T ext., 2024, 48, 511-527.custom:[[[-]]]

- 12 E. O. Alegbe and T. O. Uthman, "A Review of History, Properties, Classification, Applications and Challenges of Natural and Synthetic Dyes" , Heliyon, 2024, 10, e33646.custom:[[[-]]]

- 13 S. Safapour, R. Almas, L. J. Rather, S. S Mir, M. A. Assiri, and P . Rostamzadeh, "Functional and Photostable Textile Dyeing: a Comparative Study of Natural (Madder, Cochineal) and Synthetic (Alizarin Red S) Dyes on Wool Yarns" , J. Text. Inst., 2025, 1-15.custom:[[[-]]]

- 14 M. Chairat, V. Rattanaphani, J. B. Bremner, S. Rattanaphani, and D. F . Perkins, " An Absorption Spectroscopic Investigation of the Interaction of Lac Dyes with Metal Ions" , Dyes Pigm., 2004, 63, 141-150.custom:[[[-]]]

- 15 S. Bai, "Dyeing Conditions and Mordant Effects on the Cow Leather Dyed with Lac Powder", J. Fashion Bus., 2013, 17, 140-148.custom:[[[-]]]

- 16 Q. Huang, Z. Wang, L. Zhao, X. Li, H. Cai, S. Yang, M. Yin, and J. Xing, "Environmental Dyeing and Functionalization of Silk Fabrics with Natural Dye Extracted from Lac" , Molecules, 2024, 29, 2358.custom:[[[-]]]

- 17 A. Jimtaisong, "Aluminium and Calcium Lake Pigments of Lac Natural Dye" , Braz J. Pharm. Sci., 2020, 56, e18140.custom:[[[-]]]

- 18 N. A. A. El Sayed, M. A. El-Bendary, and O. K. Ahmed, "Sustainable Approach for Linen Dyeing and Finishing with Natural Lac Dye Through Chitosan Bio-mordanting and Microwave Heating" , J. Eng. Fibers Fabr., 2023, 18, 1-12.custom:[[[-]]]

- 19 M. Zarkogianni, E. Mikropoulou, E. V arella, and E. T satsaroni, "Colour and Fastness of Natural Dyes: Revival of Traditional Dyeing Techniques" , Color Technol., 2010, 127, 18-27.custom:[[[-]]]

- 20 Y. W. Ko and H. J. Yoo, "Dyeability of Fabrics Using Indian Dyestuffs of Madder, Marigold and Pomegranate", J. Korean Soc. Clothing Text., 2014, 38, 929-941.custom:[[[-]]]

- 21 L. Guo, Z. Y. Yang, R. C. Tang, and H. B. Yuan, "Preliminary Studies on the Application of Grape Seed Extract in the Dyeing and Functional Modification of Cotton Fabric", Biomolecules, 2020, 10, 220.custom:[[[-]]]

- 22 S. V . J. Berbers, D. Tamburini, M. R. van Bommel, and J. Dyer, "Historical Formulations of Lake Pigments and Dyes Derived from Lac: A Study of Compositional Variability" , Dyes Pigm., 2019, 170, 107579.custom:[[[-]]]

- 23 J. Han, E. Shim, and H. R. Kim, "Effects of Cultivation, Washing, and Bleaching Conditions on Bacterial Cellulose Fabric Production" , Text. Res. J., 2019, 89, 1094-1104.custom:[[[-]]]

- 24 J. E. Song, J. Su, A. Loureiro, M. Martins, A. Cavaco-Paulo, H. R. Kim, and C. Silva, "Ultrasound‐assisted Swelling of Bacterial Cellulose" , Eng. Life Sci., 2017, 17, 1108-1117.custom:[[[-]]]

- 25 Y. Togo and M. Komaki, "Lac Dyeing Cotton Fibers by Pretreating with Tannic Acid and Aluminum Acetate", Text. Res. J., 2011, 81, 111-112.custom:[[[-]]]

- 26 Y. Togo and M. Komaki, "Effective Lac Dyeing of Cotton Fabric by Pretreating with Tannic Acid and Aluminum Acetate" , Sen'i Gakkaishi, 2010, 66, 99-103.custom:[[[-]]]

- 27 N. Tanikawa, H. Inoue, and M. Nakayama, " Aluminum Ions Are Involved in Purple Flower Coloration in Camellia japonica ‘Sennen-fujimurasaki’" , Hortic J., 2016, 85, 331-339.custom:[[[-]]]

- 28 G. S. Townsend and B. W. Bache, "Kinetics of Aluminium Fluoride Complexation in Single- and Mixed-ligand Systems" , Talanta, 1992, 39, 1531-1535.custom:[[[-]]]

- 29 S. Rattanaphani, M. Chairat, J. B. Bremner, and V. Rattanaphani, " An Adsorption and Thermodynamic Study of Lac Dyeing on Cotton Pretreated with Chitosan" , Dyes Pigm., 2007, 72, 88-96.custom:[[[-]]]

- 30 S. M. Choi and E. J. Shin, "The Nanofication and Functionalization of Bacterial Cellulose and Its Applications" , Nanomater, 2020, 10, 406.custom:[[[-]]]

- 31 J. Minn, H. Kim, and H. R. Kim, "Bacterial Cellulose Crosslinked with Citrus Peel: A Multifunctional Leather Substitute" , J. Nat. Fibers, 2025, 22, 2526095.custom:[[[-]]]

- 32 N. Kiangkitiwan and K. Srikulkit, "Preparation and Properties of Bacterial Cellulose/graphene Oxide Composite Films Using Dyeing Method" , Polym. Eng. Sci., 2021, 61, 1854-1863.custom:[[[-]]]

- 33 X. Liu, L. Cao, S. Wang, L. Huang, Y. Zhang, M. Tian, X. Liu, and J. Zhang, "Isolation and Characterization of Bacterial Cellulose Produced from Soybean Whey and Soybean Hydrolysate" , Sci. Rep., 2023, 13, 16024.custom:[[[-]]]

- 34 S. Y . Oh, D. I. Y oo, Y . Shin, H. C. Kim, H. Y . Kim, Y . S. Chung, W . H. Park, and J. H. Y ouk, "Crystalline Structure Analysis of Cellulose Treated with Sodium Hydroxide and Carbon Dioxide by Means of X-ray Diffraction and FTIR Spectroscopy" , Carbohydr. Res., 2005, 340, 2376-2391.custom:[[[-]]]

- 35 A. K. Deb, M. A. A. Shaikh, M. Z. Sultan, and M. I. H. Rafi, "Application of Lac Dye in Shoe Upper Leather Dyeing", Revista de Pielarie Incaltaminte, 2017, 17, 97.custom:[[[-]]]

- 36 P. Nacowong and S. Saikrasun, "Thermo-oxidative and Weathering Degradation Affecting Coloration Performance of Lac Dye" , Fashion Text., 2016, 3, 1-16.custom:[[[-]]]

- 37 Z. Jaworska and T. Urbanski, "Infrared Spectroscopic Investigation of Metal Complexes of 1-Hydroxyanthraquinone" , Bull. L ’ Academie Pol. des Sci., 1969, 17, 579-585.custom:[[[-]]]

- 38 D. Bhatia, M. Alam, and P. C. Sarkar, "Specular Reflectance and Derivative Spectrometric Studies on Lac‐epoxy Resin Blends" , Pigm. Resin. Technol., 2007, 36, 18-29.custom:[[[-]]]

- 39 D. Bhatia, P. C. Sarkar, and M. Alam, "Specular Reflectance and Derivative Spectrometric Studies of Lac‐Phenol Formaldehyde Resin Blends" , Pigm. Resin. Technol., 2006, 35, 205-215.custom:[[[-]]]

- 40 J. N. Chakraborty in "Handbook of Textile and Industrial Dyeing" (M. Clark Ed.), Woodhead Publishing, Sowston, 2011, pp.446-465.custom:[[[-]]]

- 41 J. Minn, H. Kim, B. H. Lee, and H. R. Kim, "Improved Flame Retardancy of Bacterial Cellulose Fabrics Treated Using the Plant-Based Materials Banana Peel, Beet, and Spinach" , J. Nat. Fibers, 2024, 21, 2436053.custom:[[[-]]]

- 42 F. Batool, S. Adeel, M. Azeem, A. A. Khan, I. A. Bhatti, A. Chaffar, and N. Iqbal, "Gamma Radiations Induced Improvement in Dyeing Properties and Colorfastness of Cotton Fabrics Dyed with Chicken Gizzard Leaves Extracts" , Radiat. Phys. Chem., 2013, 89, 33-37.custom:[[[-]]]

- 43 S. Janhom, R. Watanesk, S. Watanesk, P. Griffths, O. A. Arquero, and W. Naksata, "Comparative Study of lac Dye Adsorption on Cotton Fibre Surface Modified by Synthetic and Natural Polymers" , Dyes Pigm., 2006, 71, 188-193.custom:[[[-]]]